Measuring elite persistence

Rising inequality in the latter part of the 20th century has brought questions of class and social mobility solidly back onto the academic research agenda. Sub-Saharan Africa remains on the fringes of these inequality and mobility debates due to the dearth of data with which to measure such processes of social change. A priori, there are reasons to think that processes of elite formation and perpetuation differ in 20th century Africa compared to other parts of the world, as private property rights remain circumscribed in many rural settings, families large, and severe economic and political shocks have undermined capital accumulation.

Can the use of non-traditional sources allow us to make more headway in understanding how post-colonial elites were formed and how they have persisted? In a recent article, we explore whether and how name analysis research can be applied to study social mobility and elite persistence in an African context, building on methods developed by Clark and Cummins (2014).

Elite communities in Sierra Leone

With a focus on Sierra Leone, we identify surnames associated with two communities that dominated elite positions in colonial times: Chiefly families and descendants of Krio settlers. We measure how overrepresented these name groups are across elite types (political, economic and educational) and time, relative to their frequency in the general population.

Sierra Leone has an atypical history as a site of resettlement for freed slaves in the late 18th and 19th centuries. Today, however, the descendants of these previously enslaved settlers are an upper stratum with higher socioeconomic status than the national average. Consequently, Sierra Leone presents a case where the elite is dominated by descendants of settlers that were of non-elite origin. In the larger interior protectorate, moreover, the British established a system of indirect rule that governed through- and formalised the powers of precolonial rulers, who became Paramount Chiefs.

Since independence the country has suffered a tumultuous postcolonial path that has included successive coups, a one-party state, a severe economic collapse and a devastating civil war. Consequently, Sierra Leone combines a colonial history characterised by marked social cleavages (between the Creole and indigenous population, and between the Chiefly families and commoners), with a succession of postcolonial shocks that might – hypothetically – have weakened the pre-existing social hierarchy.

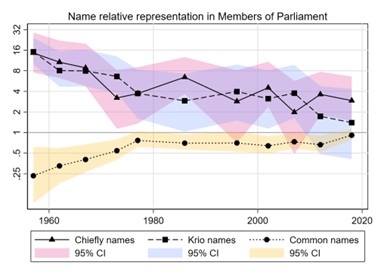

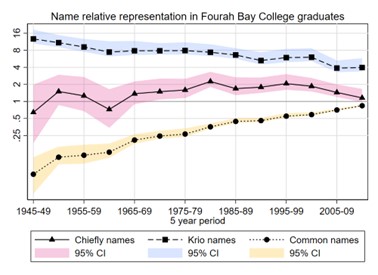

Evidence of elite persistence and elite compartmentalisation

Our findings show that despite this turbulent postcolonial path, historical elite groups have persisted and persisted in their colonial-era spheres. Figure 1 and 2 measure how overrepresented Chiefly and Krio names are, relative to their population share, amongst Members of Parliament and university graduates. An overrepresentation of 2 for instance, means the name group is twice as large in the elite sample, as in the population at large. We contrast these two elite name groups with a group of the most common surnames in Sierra Leone. This shows that both elite groups started with pronounced overrepresentation in parliament the late colonial period (roughly 15 times their share of the general population). The overrepresentation fell markedly in the decade after independence, but has remained relatively steady at around 3 for the Chiefly name-holders, while in the last two elections it has approached one for the Krio name-holders, implying that the Krio are no longer overrepresented. Common name-holders, conversely, started with a marked under-representation, but are converging towards one. Among university graduates, the Krio name-holders started with an overrepresentation of around 15 times their population share, and still remain markedly overrepresented today with an overrepresentation of four. Chiefly name-holders in contrast, were never that overrepresented to begin with, but gained relative to common name-holders in the early independence period, before converging to one (which suggests very little overrepresentation) today.

Figure 1. Relative representation among Members of Parliament

Figure 2. Relative representation among university graduates

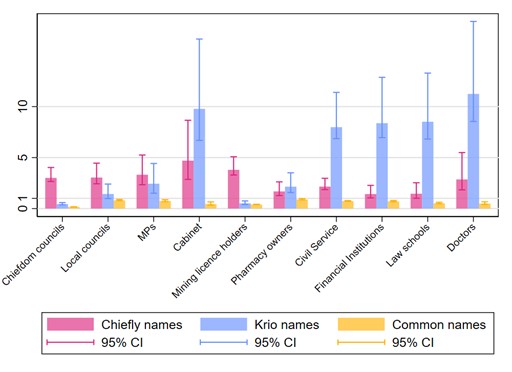

The patterns of overrepresentation for these two groups thus differ. Figure 3 measures average overrepresentation across a range of elite occupations in the 2000s. The Krio remain strongly overrepresented in the professions, civil service and business community, and their level of overrepresentation is higher the more educationally-selective the profession. Chiefly names in contrast are strongly overrepresented in politics and the mining sector, but less so in the civil service and professions. This evidence speaks not only to considerable elite persistence, but also to strong persistence in the type of career paths pursued by members of different elite communities.

Figure 3. Relative representation across various occupations, 2000s

We also measure the rate at which the overrepresentation declines, which can be interpreted as a rate of social mobility, and compare this to other elite name groups from around the world where similar methods have been deployed, including India, Sweden and the United Kingdom (Clark, 2014). This suggests that Sierra Leone’s elites have similar levels of educational persistence to comparable groups around the world, although Sierra Leone’s parliamentarians has seen higher rates of turnover than in the U.K.

Conclusions

In comparative perspective, Sierra Leone does not stand out for the openness of its elites. This is an interesting result, given the obstacles to wealth accumulation in Sierra Leone, and the extreme economic and political instability since independence. It points to the varied ways in which elite status can be protected and transmitted, despite political and economic volatility. Indeed, the mechanisms of elite persistence have been distinct for the two groups we study, involving greater investments in human capital by the Krio group, and investments in local political power and social networks for chiefly families.

References

Clark, G. (2014). The Son Also Rises: Surnames and the History of Social Mobility, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Clark, G. & Cummins, N. (2014). ‘Surnames and Social Mobility in England, 1170–2012’, Human Nature, 25(4), 517–537.

Feature image: Elite Krio Family, c.1918, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 License.