Previous research on the changing property rights associated with colonialism has focused on three groups of agents: colonial governments, indigenous populations, and settlers. The role of corporations in redefining property rights during colonization is, in contrast, under-researched. Our article contributes to this field by comparing two colonies on the periphery of the British Empire: Northern Rhodesia (present-day Zambia) and Nyasaland (present-day Malawi). Unlike in the core of the British Empire, modern property rights were not well-defined on the frontier of the empire and underwent drastic redefinition during colonial expansion.

The article shows how a key corporate actor in this region – the British South Africa Company (BSAC) – made claims to vast tracts of land and to mineral rights in the region. The company had been granted a charter by the British Imperial Government whereby it could make claim to such rights, but only if it had entered into treaties with local rulers in the region. The problem, we show in the article, was that the company made claims to land and minerals for which it could not show proof of any treaty with the local ruler in question.

Chartered companies in Africa

Chartered companies were key tools for European overseas colonization and a means for European governments to “outsource empire”, as Phillips and Sharman (2020), have argued. Chartered companies were an innovation from the early modern period, and were the legal form used by gigantic companies like the English and Dutch East India Companies. While some of the most famous chartered companies were dissolved during the eighteenth and early nineteenth century for various reasons, the legal form of chartered companies came into widespread use again in the late nineteenth century, not the least in the European colonization of Sub-Saharan Africa, and was at this time granted to several British, German and Portuguese companies.

One of the most important of these was the British South Africa Company, chartered in 1889, under the leadership of the (in)famous Cecil Rhodes. The company eventually colonised the territories that today form Zambia, Zimbabwe and (parts of) Malawi. The company lost its royal charter in 1923 but survived as a corporation until the 1960s (Rönnbäck and Broberg 2022). Our article focuses on the period from 1923 to 1950, after the end of chartered rule. This was a period when the BSAC supposedly did not enjoy any special privileges from the British Imperial Government.

Main Findings

We show empirically that the British Imperial Government, in time, became fully aware of the lack of legal basis for the concessions claimed by the BSAC. In some cases chiefs had supposedly granted land and mineral rights to territories they had no suzerainty over (e.g., the Lewanika Concession signed by King Lewanika, in Northern Rhodesia, extended to regions in the Copperbelt where the latter had no dominion). Other factors that were discovered were the use of illiterate chiefs and deception by the company.

In internal documents from the British Imperial Government, government officials labelled the company’s claims “dubious”. But despite being aware of the dubious nature of the claims, and the company’s failure to provide titles to its claims, the government did not revoke the company’s property rights but rather chose to help the company legitimize the claims. There were several reasons why the British Imperial Government acted this way.

For one thing, revoking the dubious claims would damage the reputations of both the BSAC and the British Imperial Government. If it became publicly known that the British Imperial Government had accepted what effectively was massive land grabbing, that could lead to enormous consequences for colonial rule throughout the Empire.

A more specific reason was that multinational corporations had invested vast sums of money in the region, particularly in the copper-rich Copperbelt region in Northern Rhodesia. These investments had been made under the belief that the BSAC held genuine title to the mineral rights and could alienate those rights to others. If the underlying property rights were allowed to be questioned, that would have cast shadows on the assets of all these other investors, too.

A third reason, important in the case of Nyasaland, was that the British Imperial Government legitimized the company’s interests since the company otherwise would demand payments on taxes that it had paid to the British crown for the land it claimed property rights to.

The findings in our article contrast those of previous scholars studying the region’s history. For instance, unlike Peter Slinn (Slinn 1971, 375–76) who argued that the British Imperial Government did not know or appreciate the value of the property rights in Northern Rhodesia, we show that they were fully aware of it. In contrast to Owen Kalinga’s previous research on Nyasaland (Kalinga 1984), which argued that the BSAC gave up its land rights in that colony because it saw little prospect for development, we find that the real reason was rather a recognition that its property rights were dubious and would hardly withstand a process of litigation.

Conclusion

Overall, we show that the BSAC was able to wield significant influence over these political processes and that the interests of the African communities, settlers, and the broader public were subjugated. That is, the British Imperial Government favoured the interests of a corporation it acknowledged had no legal basis for the claims of ownership. In essence, this shows how the British Imperial Government of the time fell prey to regulatory capture.

References

Kalinga, Owen JM. 1984. “European Settlers, African Apprehensions, and Colonial Economic Policy: The North Nyasa Native Reserves Commission of 1929.” International Journal of African Historical Studies, 641–56.

Phillips, Andrew, and J. C. Sharman. 2020. Outsourcing Empire : How Company-States Made the Modern World. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rönnbäck, Klas, and Oskar Broberg. 2022. “From Defensive to Transformative Business Diplomacy. The British South Africa Company and the End of Chartered Company Rule in Rhodesia, 1910–1925.” Business History Review 96 (4): 777–804.

Rönnbäck, K., & Ngoma, K. H. (2024). Regulatory capture in the British Empire: The British South Africa Company and the redefinition of property rights in Southern Africa. Business History, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2024.2349685

Slinn, Peter. 1971. “Commercial Concessions and Politics during the Colonial Period: The Role of the British South Africa Company in Northern Rhodesia 1890-1964.” African Affairs 70 (281): 365–84.

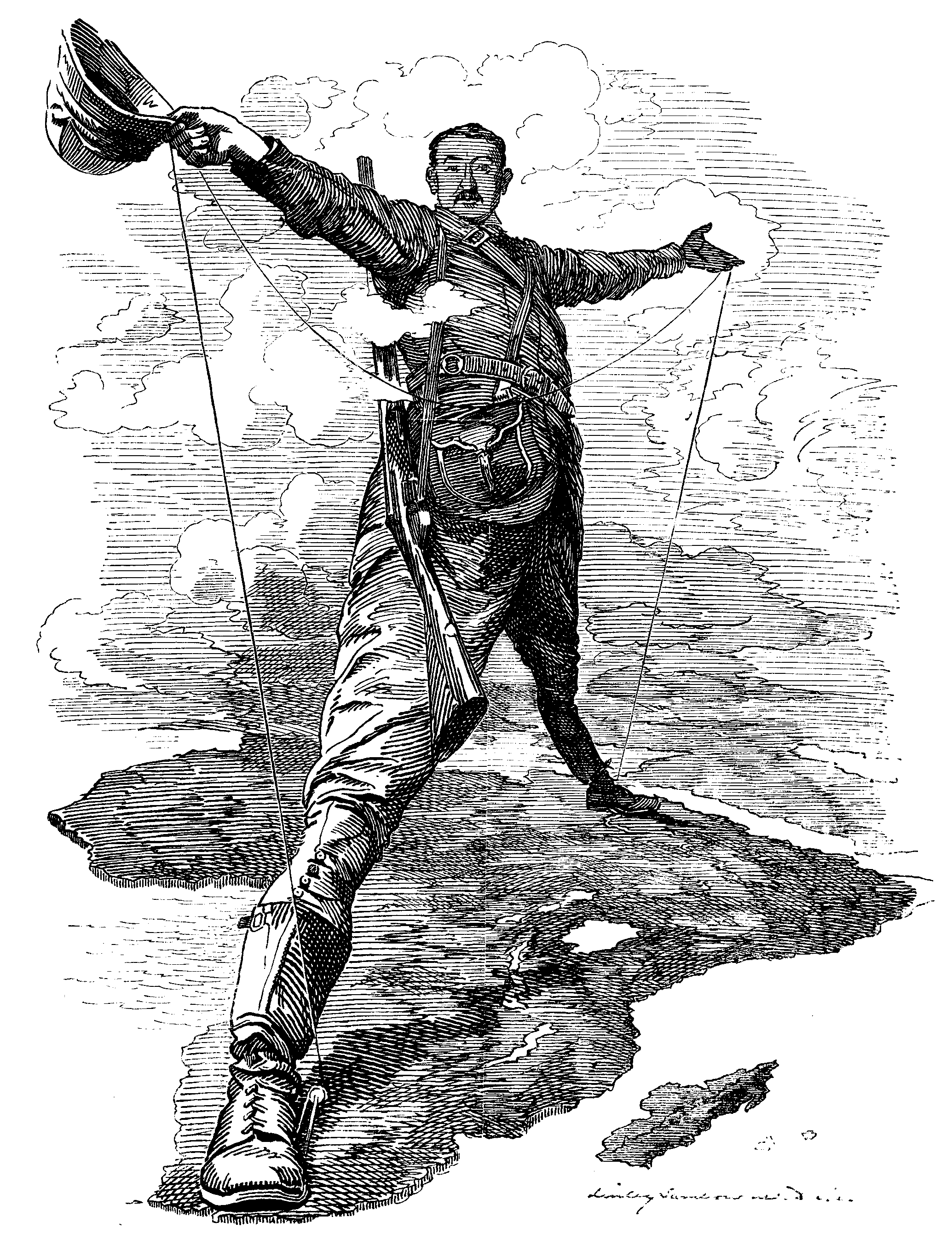

Feature image is the Colossus of Rhodes: Striding From Cape To Cairo by Edward Linley Sambourne, from Punch Magazine of 1892