What can we learn from studying intermarriage shares?

The shares of intermarriages have long been used to study the salience of cleavages within societies (Kalmijn 1998). Looking at marriage patterns gives us a sense of who meets whom and of who is thought of to be an acceptable match. In a recent paper (Crespin-Boucaud 2020), I study interethnic and interfaith marriage patterns in sub-Saharan Africa.

Since the publication of Easterly and Levine’s (1997) seminal paper, an extensive literature has debated whether ethnicity matters for economic and political outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa, yet little is known about how ethnicity matters to individuals’ everyday lives. As marriage is arguably one of the biggest welfare-impacting decisions an individual can make (Becker 1974), if ethnic identity matters to people, ethnicity should also influence marriage markets. Ethnicity is often thought of as an unalterable characteristic that is transmitted from parents to children (Chandra 2006). In contrast, religious identity in African countries is more fluid due to the possibilities of conversion. The interfaith marriage shares we observe are therefore lower bound estimates, as we only consider marriages in which spouses did not convert before marriage. If ethnic (religious) identity matters to individuals, then we would expect low shares of intermarriages along this identity dimension, as marrying within one’s group makes it more likely that ethnic (religious) identity is transmitted to the next generation (Bisin & Verdier 2000).

To examine these phenomena, I compare patterns of interethnic and interfaith marriages. I use Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) from 15 countries for which information on respondents’ ethnic identity was collected. I use ethnic classifications that are country-specific, but a religious classification that is common to all countries. Respondents are classified as either Christian, Muslim, or African traditional religions and other beliefs.

Marriages across ethnic and religious lines: far from rare

Interethnic unions are on average more frequent than interfaith unions. Across my sample of 15 counties, 20.4% of women are married to a man who is not from the same ethnic group, while 9.7% of women are married to a man who is not a member of the same religious group. Muslim-Christian marriages are extremely rare, making up only 2.1% of marriages.

However, the share of intermarriages will be driven by the number of categories used and their respective shares of the population. For instance, if there is little religious diversity in a country, there cannot be many interfaith unions. To capture levels of diversity in a country, I therefore compute random shares of intermarriages as comparators, which measure the share of intermarriages we would observe if people were matched at random on the marriage market.

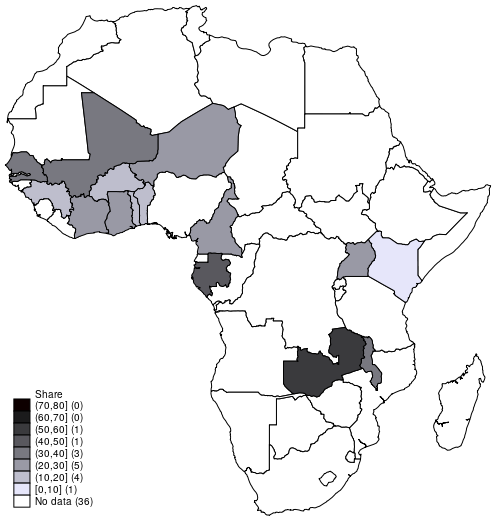

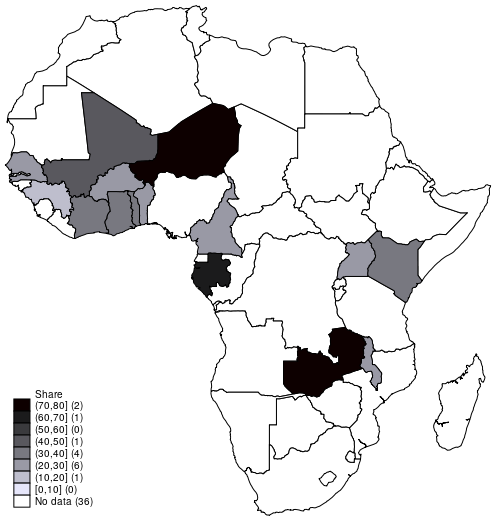

Under random matching, across the entire sample we would expect that roughly 80% of marriages would be interethnic and around 34% would be interfaith. When we look at the ratio of the observed share of intermarriages to the random share of intermarriages, interfaith marriages and interethnic marriages are roughly as common: between 25% and 30% of the random share of intermarriages is realized. Figure 1 shows the ratio of observed interethnic (interfaith) marriage shares to random interethnic (interfaith) shares. The lowest ratio of interethnic marriages is found in Kenya and the highest in Zambia. The lowest ratio of interfaith marriages are observed in Guinea and the highest in Gambia, Niger, and Zambia.

Figure 1: Shares of interethnic and interfaith marriages

Notes: Left panel: Ratio of observed share to random share of interethnic marriages. Higher ratios mean that the share of interethnic marriages is closer to what would be observed under random matching. Right panel: Ratio of observed share to random share of interfaith marriages. Higher ratios mean that the share of interfaith marriages is closer to what would be observed under random matching. Data: Survey wave (DHS) conducted the closest to 2005. Sample: Women currently in union.

Time trends

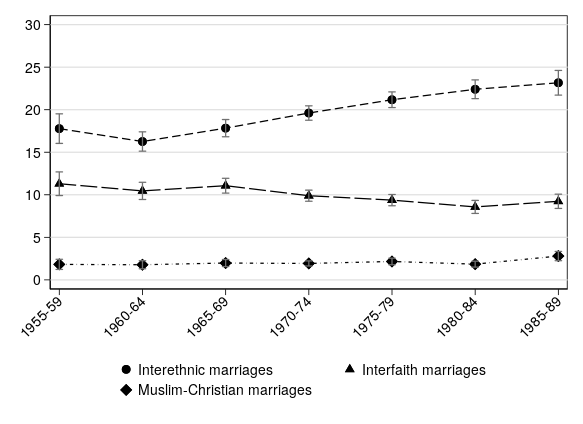

Figure 2 shows the shares of each type of intermarriage by birth cohort of women, thus illustrating the rate of change in intermarriage shares. It shows that the share of interethnic marriages has increased over time in the pooled sample. There is no country where interethnic marriages have become less frequent. The share of interfaith marriages, in contrast, decreased in the pooled sample. Only in Cameroon did interfaith marriages become more frequent. The share of Muslim-Christian marriages remained stable.

Figure 2: Intermarriage shares on pooled sample

Notes: Observed share of intermarriages by birth cohort of women. 95% confidence intervals included. Data: Pooled & reweighted sample of 15 countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo, Uganda, and Zambia. Sample: Women currently in union.

Notes: Observed share of intermarriages by birth cohort of women. 95% confidence intervals included. Data: Pooled & reweighted sample of 15 countries: Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Malawi, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo, Uganda, and Zambia. Sample: Women currently in union.

Increasing interethnic marriage shares are likely to be due to the combined effects of increased education levels, urbanization, and changes in norms. Using regression analysis to examine the correlates of being in an interethnic marriage shows an increase in interethnic marriage shares of 4.2 percentage points between the cohort born in 1960 cohort and the one born in 1985, even after education and urban residence are controlled for. Increased mixing and changes in preferences and norms are likely to be driving this effect. In contrast, interfaith marriages have decreased due to a decrease in the share of people identifying with faiths other than Islam and Christianity, in particular the decline in identification with traditional African religions. Thus there is no indication of a change in norms around interfaith marriages.

Studying interethnic marriages allows us to qualify some assumptions made about ethnic identity in sub-Saharan Africa. Most of the economic literature assumes that individuals belong to only one ethnic group. The high shares of interethnic marriages suggest that it is important to collect ethnic data in ways that allow people to tick multiple identity boxes and allow for a more nuanced understanding of ethnicity-based identities. These considerable rates of intermarriage in sub-Saharan Africa shows that group differences are not always barriers to marriage.

References

Becker, G. S. (1973). A theory of marriage: Part I. Journal of Political Economy 81(4): 813-846.

Bisin, A., & Verdier, T. (2000). ’Beyond the melting pot’: Cultural transmission, marriage, and the evolution of ethnic and religious traits. Quarterly Journal of Economics 115(3): 955-988.

Chandra, K. (2006). What is ethnic identity and does it matter? Annual Review of Political Science 9: 397-424.

Crespin-Boucaud, J. (2020). Interethnic and interfaith marriages in sub-Saharan Africa. World Development 125, forthcoming.

Easterly, W., & Levine, R. (1997). Africa’s growth tragedy: Policies and ethnic divisions. Quarterly Journal of Economics 112(4): 1203-1250.

Kalmijn, M. (1998). Intermarriage and homogamy: Causes, patterns, trends. Annual Review of Sociology 24(1): 395-421.

Feature image: Photo by Andrew Itaga (taken in Uganda) on Unsplash.