The optimal way of using the proceeds from mineral discoveries continues to elude many developing countries. Because such discoveries can fuel rapid economic growth, one of the key challenges that emerge is how to design tax systems that tap substantially into the mining wealth without strangling the proverbial goose. Such tax revenue would allow countries to deliver public services and invest in infrastructure, for example, buttressing the processes of industrialization and development. This seems simple but the reality is often very different. We study one such episode: the Cape Colony, a major British colony in southern Africa after the discovery of minerals. To do so, we reconstructed taxation, expenditure, and public debt data from 1820 to 1910.

Public revenue and expenditure

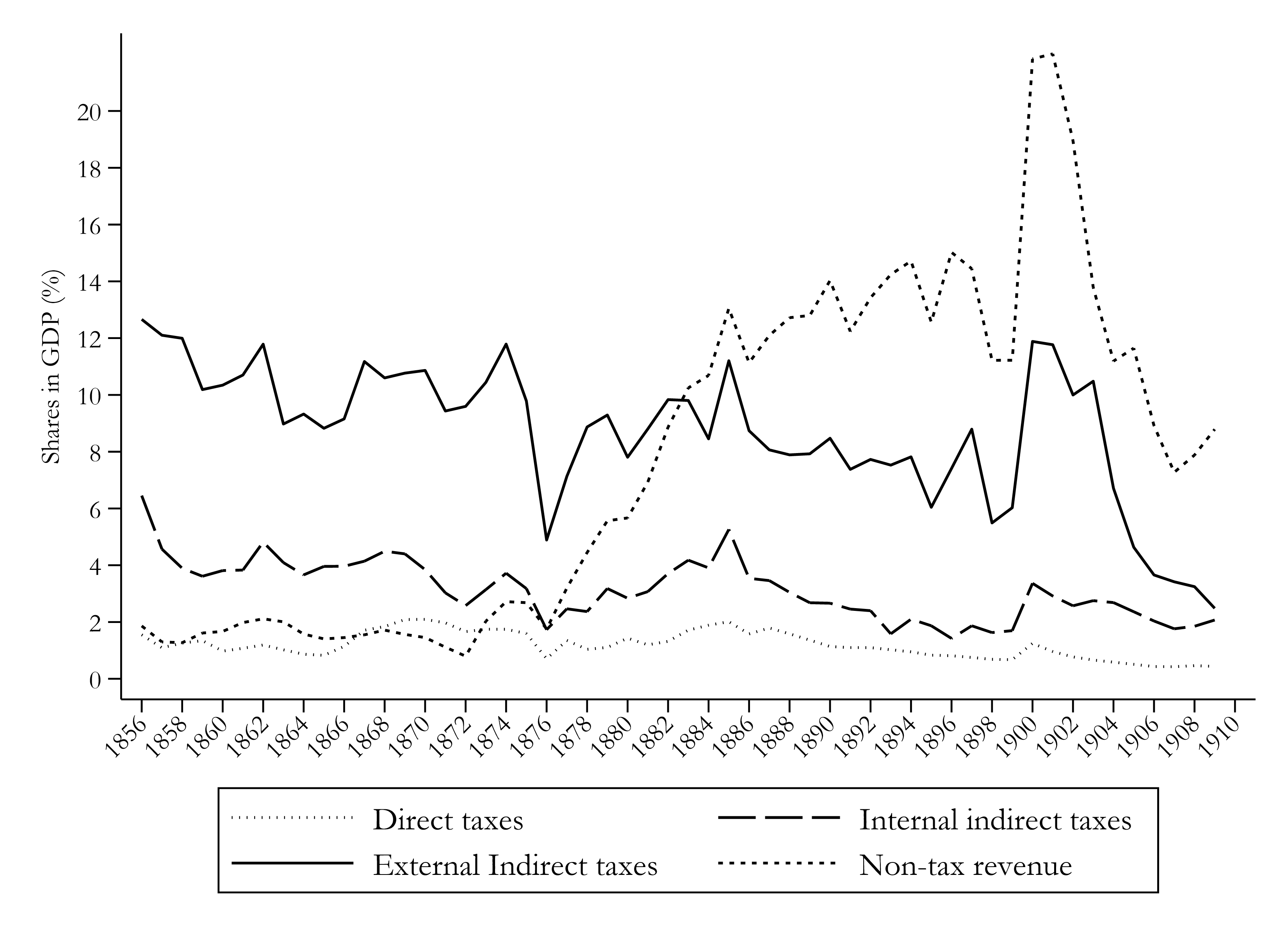

Prior to the discovery of diamonds in 1867, the economic progress of the Cape was steady rather than spectacular (Ross 1983). It was the discovery of diamonds and, two decades later, gold in the southern African interior that put the Cape Colony onto the same development trajectory as the Australian colonies which had significant gold rushes. Research has shown that in Australia, mineral beneficence played important roles not only for ‘democratic’ consolidation (Brunkova & Shanahan 2019, p. 28), but royalties, profit taxes and license fees became major sources of government revenues (McLean 2012). Despite recent research showing diamond mining, through the De Beers company, produced unusually high profits in South Africa (Rönnbäck & Broberg 2019, p. 244), the effects of the mineral revolution on the Cape’s finances remained unclear. Our recent work on the evolution of taxation, public expenditure and debt bring important insights on this (Gwaindepi 2018; Gwaindepi & Fourie 2020; Gwaindepi & Siebrits 2020). On the revenue side, Figure 1 shows the Cape Colony’s tax and non-tax revenues sources relative to GDP.

Figure 1: Direct, indirect and non-tax revenues as shares in GDP, Cape Colony

It transpires that the GDP shares of all the tax revenue categories decreased over the late 19th century. The normal pattern, which has been identified as an important aspect of the establishment of durable states (Hoffman, 2015), is that national income growth is accompanied by increases in the tax-to-GDP share (Besley & Persson 2014). The opposite pattern of the Cape suggests that the tax structure did not transform to take advantage of growing incomes. By contrast, non-tax revenues increased as percentages of GDP from around 1870 onwards, especially because the newly established railway system generated substantial revenue, through carrying goods and people to and from the mining fields. The reliance on alternative non-tax sources has been found to undermine fiscal capacity building (Albers, Jerven & Suesse 2020). Although revenue creation was not the primary purpose of the railway system, its receipts proved to be indispensable in the context of the meagre yields of the tax system. Most notably, an income tax was not implemented until 1904; the Colony used the state-owned railway system to indirectly tap the growing incomes and wealth instead. When customs and railway revenues plummeted after the war which to place in the whole of South Africa, generally referred to as the South African war. In this period the budget deficits that had plagued the Cape Colony since 1880 became unsustainable despite the belated introduction of an income tax.

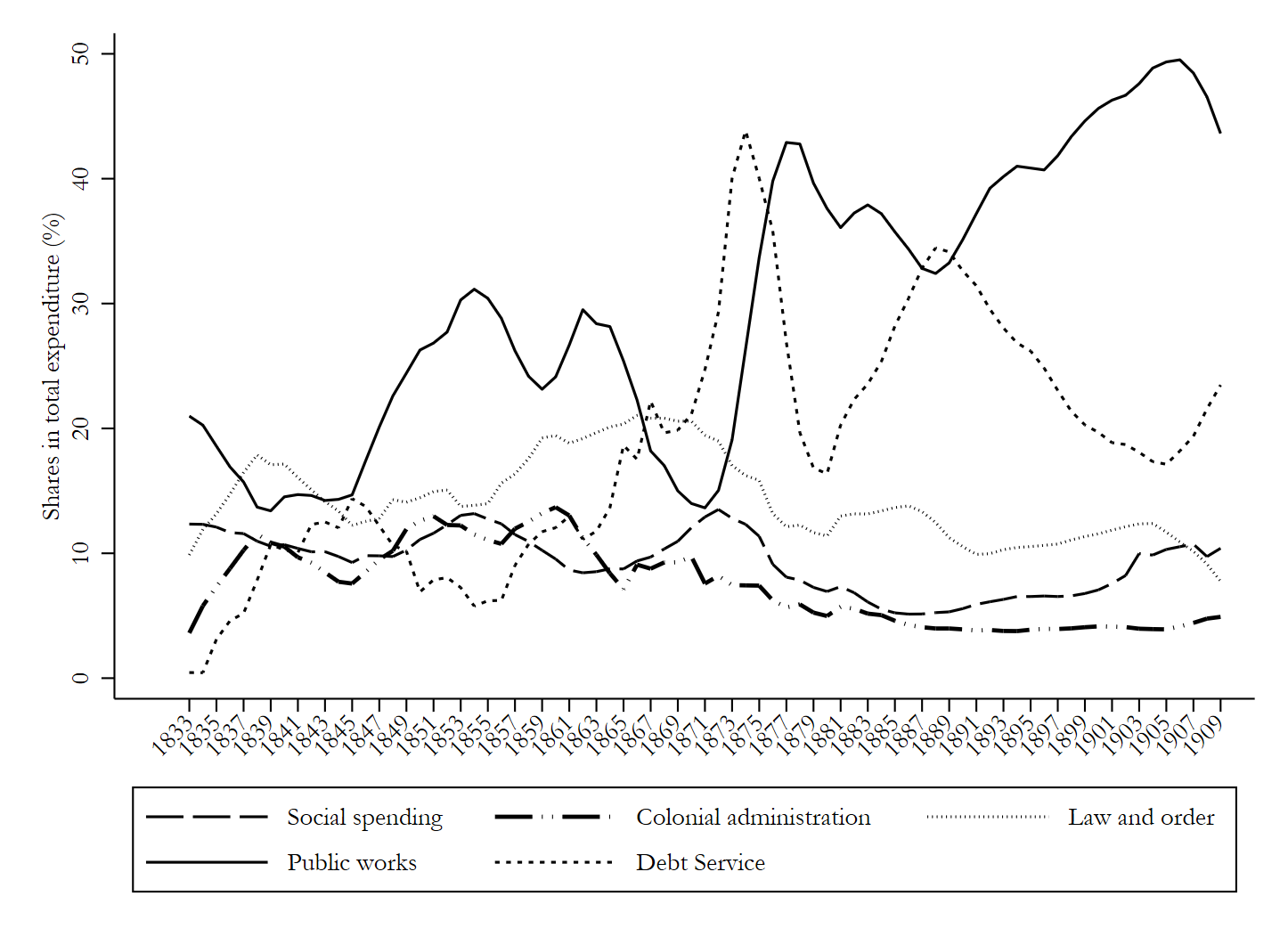

On the public expenditure side, infrastructure was a major priority for the government. But as can be seen from Figure 2, the infrastructure (public works) priorities changed substantially over the 19th century, notably after the discovery of diamonds and the construction of a railway line from Cape Town to Kimberley. Between 1873 and 1910, the miles of tracks increased from below 100 miles to over 3,000 miles (Herranz-Loncan & Fourie 2018).

Figure 2: Functional classification of public expenditure, 1833-1909

Public debt

With meagre revenues, borrowing was inevitable. While physical capital accumulation in colonies required substantial capital beyond ordinary revenues, the servicing of the debt became a significant drain on state revenues (Figure 2), exposing the Cape’s weak fiscal capacity. The debt was inevitably linked to railway projects; at least 65% of the accumulated debt by 1900 was connected to the Cape Government Railways (CGR).

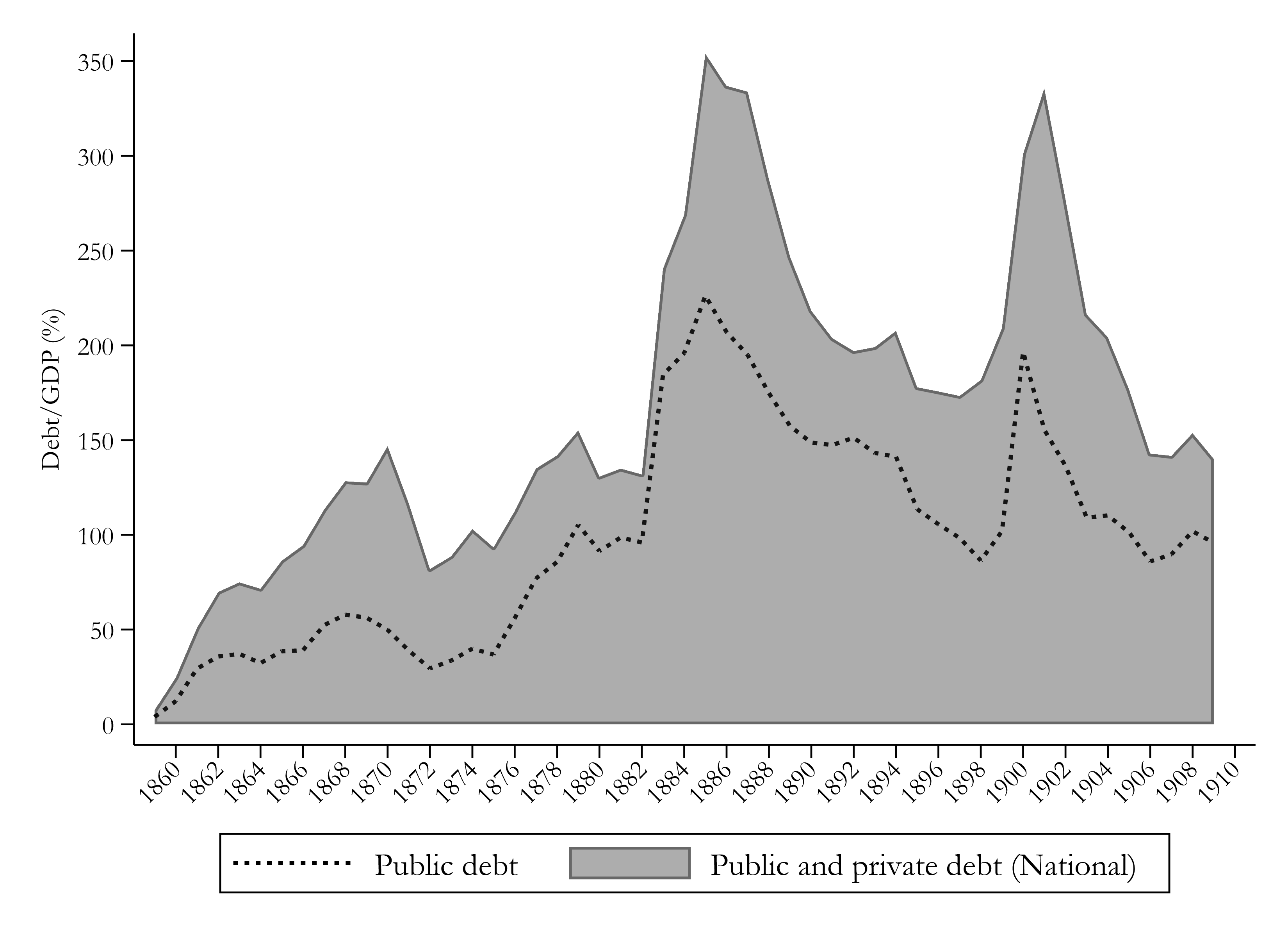

Figure 3: The Cape Colony’s debt accumulation

Figure 3 shows two phases of high levels of borrowing. The first was the 1872-1882 period which was due to an acceleration of railway construction towards Kimberley. The second phase, 1898-1901, was the war period, given that GDP had declined in the duration of the war. While the extension of branch lines motivated borrowing during this second phase, the high interest payments necessitated more borrowing because dwindling ordinary revenues were no longer enough to meet all expenses.

Conclusion

The analysis of the tax and non-tax revenues of the British Cape Colony demonstrates how vested interests can stymie the diversification of the tax systems in weakly developed political systems. Given that no royalties, profit taxes nor diamond export taxes were paid to the Cape government, the biggest beneficiary of public expenditure was the smallest contributor to the public coffer. The expenditure side shows that the same interests may skew the public expenditure policies in a manner that cause uneven development when infrastructure follows precious minerals to the neglect of other sectors or regions. While the colonial railroads have generally tended to be extractive by being built to connect the coast to the mineral fields (Jedwab, Kerby & Moradi 2017), it is possible that modern developing countries may fail to escape this if political power is skewed to those within the extractive sectors.

References

Albers, T., Jerven, M., & Suesse, M. (2020). The Fiscal State in Africa: Evidence form One Century of Growth. African Economic History Network Working Paper No. 55.

Besley, T., & Persson, T. (2014). Why do developing countries tax so little. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(4).

Brunkova, Z., & Shanahan, M. (2019). The Australian Gold Rushes , 1850-1900: Elites, Mineral Ownership, and Democracy. In A. Sanders, P. Sandvik, & E. Storli (Eds.), The political economy of resource regualtion: An international and comparative history, 1850-2015. Vancouver: UBC Press.

Gwaindepi, A. (2018). State building in the colonial era: Public revenue, expenditure and borrowing patterns in the Cape Colony, 1820-1910. Stellenbosch University.

Gwaindepi, A., & Fourie, J. (2020). Public sector growth in the British Cape Colony: Evidence from new data on expenditure and foreign debt, 1830-1910. South African Journal of Economics 88: 341–367.

Gwaindepi, A., & Siebrits, K. (2020). ‘Hit your man where you can’: Taxation strategies in the face of resistance at the British Cape Colony, c.1820 to 1910. Economic History of Developing Regions 35(3): 171-194.

Herranz-Loncan, A., & Fourie, J. (2018). “For the public benefit”? Railways in the British Cape Colony. European Review of Economic History 22(1): 73–100.

Hoffman, P. (2015). What do states do ? The Journal of Economic History 75(2): 303–332.

Jedwab, R., Kerby, E., & Moradi, A. (2017). History, Path Dependence and Development: Evidence from Colonial Railways, Settlers and Cities in Kenya. The Economic Journal, 127(603), 1467–1494.

McLean, I. (2012). Why Australia prospered: The shifting sources of economic growth. Princeton University Press.

Rönnbäck, K., & Broberg, O. (2019). Capital and Colonialism: The Return on British Investments in Africa 1869–1969. Cham: Palgrave Mac Millan.

Ross, R. (1983). The relative importance of exports and the internal market for the agriculture of the Cape Colony, 1770-1855. Proceedings of the Symposium on the Quantification of the Import and Export and Long Distance Trade of Africa in the 19th Century, (Amsterdam-10 January).