Although it is undeniable that overall welfare was reduced because of colonialism, the evolution of some dimensions of welfare such as education, health or income has given rise to some debate. The common view is that living standards declined during colonialism (Austin 2016). However, because of changes brought in by the colonial powers such as the abolition of the internal slave trade, and investment in infrastructure and human capital, some researchers have suggested more mixed effects (for a review of the literature on colonial legacies, see this blog post). Our article sheds light to this debate by presenting new evidence on human height in 47 countries in Africa during and after the colonial era (Baten and Maravall 2021).

Height Data in Africa

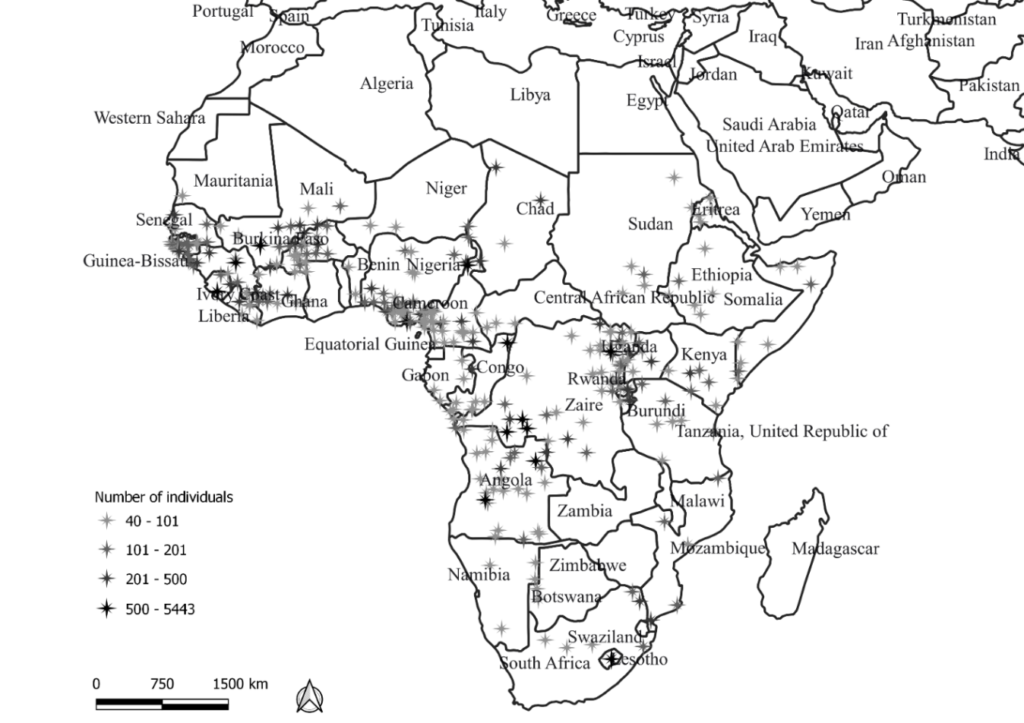

Disagreement on the impact of European colonialism on living standards has been fuelled by the scarcity of quantitative evidence. One way to deal with a lack of direct measures is to rely on biological measures such as human stature to infer past living standards. The core idea behind anthropometric studies is that average height is strongly influenced by the quality of nutrition, the prevalence of disease, and parental care level. In this study, we use an extensive new data set based on a large compilation project for heights that aimed to avoid selectivity and measurement error as much as possible (Baten and Blum, 2014). We analyse the African height data set for the first time, using 311 aggregated height values for African countries and birth decades based on 240,068 individual observations. The sources for this vast amount of data are anthropometrical studies and health surveys. As an example, Figure 1 displays the observations that we georeferenced from one of the major sources used in our study.

Figure 1. Number of observations in Hiernaux (1968)

To identify the impact of colonialism, we need to establish if a country was colonized during a specific birth decade, which is far from straightforward. Many countries had early trade settlements on islands, and only over time did the mainland become increasingly colonized; in other cases, only (coastal) parts of the territory were colonized. To make sure that we capture the various impacts of the colonization process, we rely on two different classifications of colonial status, namely, settler colonies and peasant export colonies.

Colonialism and Standards of Living of the Colonized

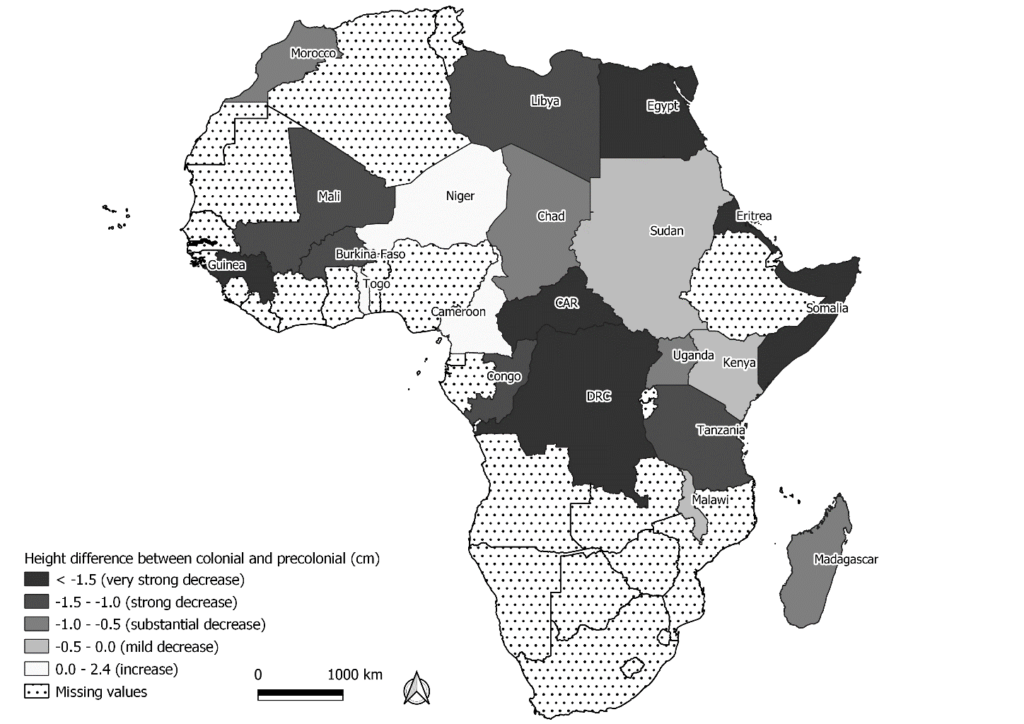

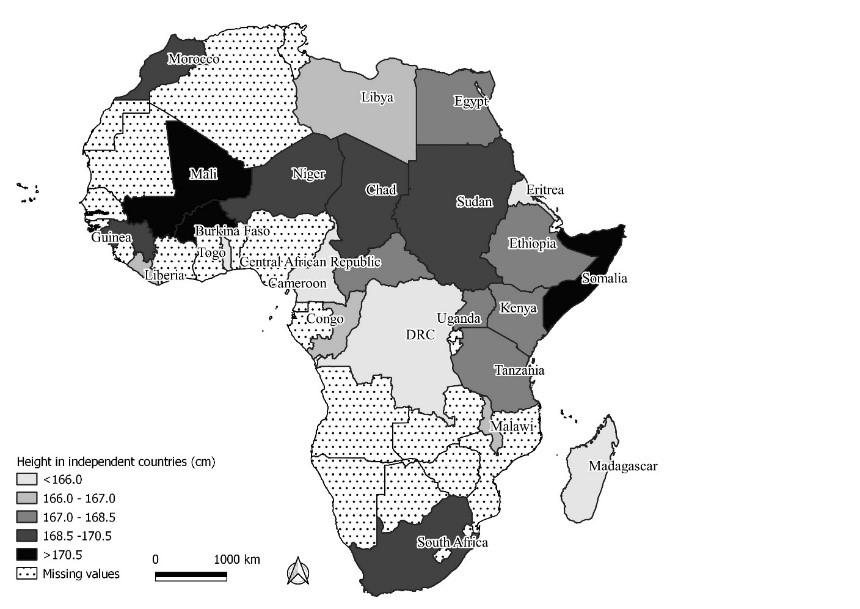

We find that the contemporary effect of colonialism was negative and significant, with a height decline of at least 1.1 cm on average across countries (Figure 2a). This decline was visible in various regions of Africa, not only in the Sahel zone where average heights were high (see Figure 2b). Our results are consistent with several hypotheses regarding the potential mechanism through which colonialism harmed development. Overall, the combined effects of a) new trade contacts spreading infectious disease, b) forced labour, c) conflicts, and d) a public health system that lacked investment and knowledge about the specific local health challenges in Africa, are likely to have resulted in low health standards during the early decades of the colonial period.

Figure 2a Height differences between colonial and pre-colonial periods

Figure 2b Heights in independent* countries, 1850-1949

*Note: This map shows average height while the countries were independent (mostly in the 1850s to 1880s period, but some countries were fully colonized only later, or not at all).

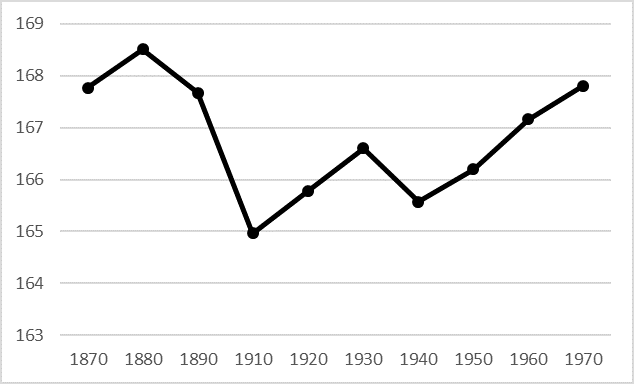

Tanzania provides an interesting example, having one of the best height records, as many waves of measurements were taken across ethnicities. We observe a height decline from the 1880s to the 1910s by more than 3 cm and not much recovery until the 1960s. The combination of conflict, infectious disease among humans and cattle, the expropriation of land, and forced labour resulted in this extreme decline. Figure 3 shows that the height effects of European colonization and the other factors (e.g., influenza, a world war) were quite drastic.

Figure 3. Height trend in Tanzania, 1870s-1970s

Overall, substantial height decline in colonial Africa is plausible based on what we know about health, forced labour, and conflict development. Diseases, such as malaria and sleeping sickness, affected many African regions. The increase in forced labour, especially during the early decades of colonialism, implied that parents could not take as much care of the medical and hygienic situation of their children as before, as they had to spend many of their days building railway lines, roads and other infrastructure (van Waijenburg, 2018). Hence, improvement in the medical situation did not progress during the first decades of colonialism. In contrast, in the early decades of colonialism, additional trade contacts resulted in greater spread of infectious diseases (Steyn, 2003). Moreover, a severe pandemic among cattle was introduced into East and South Africa and partially into West Africa during the 1890s.

The observed decline of human stature has important implications for our understanding of the welfare impact of colonialism; height tends to be strongly correlated with other dimension of human health, nutritional quality and longevity. How important was this decline of 1.1 cm? Chinese heights declined by a similar amount during the Taiping Civil War of the 1850s and 1860s, for example, one of world history ’s most devastating civil war events (Baten and Blum 2014, Figure 3). Hence a stature decline of this dimension clearly indicates that the health effects of colonization were severe for the African population.

References

Austin, G. (2016). Sub-Saharan Africa. In: Baten, J. (Ed.), A History of the Global Economy: 1500 to present. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 316–353.

Baten, J. and Blum, M. (2014). Why are you tall while others are short? Agricultural production and other proximate determinants of global heights. European Review of Economic History 18: 144–165.

Baten, J. and Maravall, L. (2021). The influence of colonialism on Africa’s Welfare: An anthropometric study. Journal of Comparative Economics (available online).

Hiernaux, J. (1968). La Diversité Humaine en Afrique Subsaharienne: Recherches Biologiques, Études ethnologiques. Editions de l’Institut de Sociologie, Université libre de Bruxelles, Brussels.

Steyn, M. (2003). A comparison between pre- and post-colonial health on the northern parts of South Africa, a preliminary study. World Archaeology 35(2): 276–288.

Van Waijenburg, M. (2018). Financing the African colonial state: The revenue imperative and forced labor. Journal of Economic History 78(1): 40–80.

Feature image: Credits to @WHOSouthSudan. This picture was taken in the context of a WHO bilharzia eradication campaign in South Sudan (2020). It bears no direct link to the content above. More information can be found here.