Zimbabwe’s industrial development has been well-studied with scholars showing opportunistic and exogenous factors such as the Great Depression, the outbreak of the Second World War, the establishment of the Central African Federation (1953-1963), and the proclamation of the UDI in 1965 as central drivers. While all these factors were important, a new book, Manufacturing in Colonial Zimbabwe, 1890-1979: Interest Group Politics, Protectionism & the State, advances that it is more fruitful to consider the role of business interest groups and the unique ‘self-governing colony’ status (autonomy) of Southern Rhodesia in shaping and determining the pace and trajectory of industrialization that earned the country the title of the second-most industrialized country in sub-Saharan Africa by 1980.

The political autonomy that Southern Rhodesia achieved in 1923 enabled its white settlers to diversify their economy in antagonism to the prevailing Imperial policy. The Imperial government’s standard practice was to promote a typical colonial development path: producing and exporting primary products and importing manufactured goods from the Metropole. The nature of this development accounts for the late diversification of economies in many colonies. Southern Rhodesia defied this trajectory because of the presence of an autonomous state that controlled the domestic economy and the existence of national industrial elites ready to lead the industrial efforts. In doing so, capital and state contested and conflicted among and against each other to diversify the economy. The book explores policy proposals and the political pressure organized industry chambers exerted on the industrialization trajectory. The expansion and diversification of industry, which took place in the former British colony, among other factors, was attributable to the efforts of industrialists, who galvanized and formed representative organizations to advance their interests, pitting them against the state and other blocs of capital – farmers, miners, and merchants.

Colonial foundations and early industrialization efforts

At its establishment, various elites constituting the state in Colonial Zimbabwe, such as international capital, farmers, miners, and merchants, believed in the supremacy of the primary exporting industries of agriculture and mining in propelling the economy. Constantly in the shadow of these two primary sectors was the manufacturing sector. The sector was so negligible that the Colony’s official Yearbook of 1932 did not mention the manufacturing industry (Arrighi, 1966). Nonetheless, visible activity occurred with the establishment of small incipient foundry and engineering firms triggered by the short-lived mining boom between 1894 and 1896 (Phimister, 1988). The incipient industries were boosted by the interruptions caused by the First World War and the Great Depression. However, this small window did not inspire a meaningful shift towards the manufacturing sector. South African industrial products quickly swarmed the local market as its industrialists capitalized on war shortages to export to Southern Rhodesia.

Britain and South Africa provided the two most important markets for the products of these two pillars of the settler economy. The local economic elite (farmers, miners, and merchants) desired to maintain trade ties with London and Johannesburg, the country’s export destinations and financial markets. This found expression through the adoption of the Imperial Preference policy. As a result, the promotion of manufacturing was looked down upon. This is unsurprising, for the Imperial powers frowned upon industrialization in colonies (Buttler, 1999).

The predominance of the mining and agriculture elite was routinely affirmed in the recommendations of Committees/Commissions instated to inquire into aspects of the Rhodesian economy. All these committees opposed assistance to the manufacturing sector. On the eve of the Second World War, Southern Rhodesia had 299 industrial units with a gross output of £5,107,000, employing 17,554 employees of all races and paid wages of £ 1,254,000 per annum. Most of these were light consumer goods industries, privately owned by domestic white capital. In comparison, gross output for mining was £7,696,000 and agriculture contributed £3,770,000. They employed 90,967 and 96,684 workers (of all races), respectively.

Second World War, the Federation, and Industrial Policy

The government’s conservative policy towards local manufacturing was rendered untenable when the Second World War broke out in 1939. This led to the statutory Industrial Development Advisory Committee (IDAC) in 1940. The IDAC advised the government to nationalize basic industries, especially those private enterprises were unwilling to take up. The government duly obliged and took over the iron and steel works at Bulawayo in 1942, set up a cotton-spinning mill at Gatooma, and nationalized the sugar refinery in 1944 (Mlambo et al., 1997; Pangeti, 1996). However, the government’s hesitancy towards the manufacturing sector again showed itself in 1946. In that year, a Commission under the chairmanship of W. Margolis to look into the protection of secondary industries recommended ‘controlled assistance’. It also concluded that the incomes of the Southern Rhodesian population still depended on the successful exploitation of the comparative advantage of producing mining and agricultural exports and that ‘the secondary industries of this Colony must, for the present, be regarded as truly of secondary importance.’

The manufacturing sector staggered on with little assistance but grew in number of firms and value. By 1948, Southern Rhodesia boasted a diversified industrial sector. In 1949, industrial elites formed the Federation of Rhodesian Industries (FRI) but still achieved little in the way of support from the government. Instead, the government’s position on industrial development was that the industry must undergo voluntary and not forced growth. Feeling let down, the FRI sought the cooperation of nascent industrialists in the two northern Federal territories to form a much wider elite industrial organization that reflected the geographical representation of the Federation. In 1957, the FRI transformed into the Association of Rhodesia and Nyasaland Industries (ARNI). Even as this happened, Southern Rhodesia industrial elites overshadowed and inhibited the expansion of industries in Northern Rhodesia because all necessary infrastructural developments and sources of manufactured goods were in Salisbury. Indeed, the manufacturing sector continued to expand in Southern Rhodesia. Between 1949 and 1957, the number of industries increased from 508 to 923 while gross output tripled from £31,076,000 to £104,945,000 over the same period. More tellingly, secondary industries’ 1957 net output of £43,176,000 was almost double the gross output of mining at £25,764,000 and slightly lower than that of agriculture at £45,086,000.

Industrial expansion and the manufacturing sector

The industrial elite continued to demand favorable industrial policy, but the government maintained that secondary industrial development remained a private enterprise. A report by the Advisory Committee on the Development of the Economic Resources of Southern Rhodesia, with special reference to African Agriculture from 1962, advised that export-oriented primary industries provided the greatest proportion of the output of the country, as well as the foreign exchange earnings necessary to finance the imports of consumer goods, raw materials, and capital equipment required to sustain the expansion of domestic industries and the standard of life of the population. Increased domestic industrial development posed a threat of increasing the cost of production for the export industries, which would vitiate their competitiveness in world markets and slow economic growth. This became the overriding consideration influencing official policy towards manufacturing.

The imposition of economic sanctions directed initially against the primary producing and exporting sectors and financial markets, coupled with the need to limit the adverse effects of declining exports, increasing unemployment and falling output and investment, dictated a more interventionist economic policy on the part of the Rhodesian Front government. More importantly, sanctions momentarily brought all the elite groups closer. The government announced in February 1966 that it would intensify its support for the manufacturing industry. Assistance would be afforded using import control for selected industries for specified periods, greater use of the customs tariff, and in special circumstances, securing the local market for one or more producers for specified periods. UDI ushered in a new period in Rhodesia’s history that presented the manufacturing sector with somewhat preferential treatment from the state. At the same time, the UDI environment also taxed industrialists’ endurance and inventiveness since the imposition of sanctions disrupted long-established patterns of trade and financial interconnections. To counter this, Rhodesia turned its focus to domestic industrial expansion. The table below shows a snapshot of the industrial report with manufacturing sectors and their output in percentage between 1967 and 1982.

Table 1. Zimbabwe´s manufacturing sector, 1967-1982.

| Subsectors | 1967 | 1975 | 1979 | 1982 |

| Foodstuffs | 24.6 | 19.7 | 23.5 | 25.0 |

| Drinks & tobacco | 9.4 | 7.0 | 7.5 | 7.4 |

| Textiles & footwear | 9.2 | 10.4 | 11.2 | 9.4 |

| Wood & furniture | 3.7 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.2 |

| Paper, printing, etc. | 5.8 | 5.7 | 4.7 | 5.2 |

| Chemicals, petroleum, etc. | 13.3 | 14.0 | 13.2 | 14.8 |

| Non-metallic minerals products | 3.1 | 3.7 | 2.6 | 3.6 |

| Metals & products | 14.5 | 22.1 | 21.5 | 18.1 |

| Electrical, machinery | 4.1 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 3.0 |

| Transport equipment | 2.8 | 3.9 | 2.7 | 3.0 |

| Other | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Total manufacturing | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: Data from the 1987 World Bank report on Zimbabwe´s industrial progress (see page 191 in the book)

A further expansion of 14% in 1970 brought the total output value to more than $580 million. Foreign currency restraints later dampened manufacturing growth in 1971. The manufacturing sector’s contribution to GDP declined from 19.4% in 1970 to 16.2% in 1971. Nevertheless, the manufacturing sector’s performance was satisfactory, especially in light of the foreign exchange restraints on imported materials. However, 65 % of these products in 1970 were monopoly products, which probably would not be able to survive a return to competitive conditions. In 1972, 98 firms (representing 7.6% of all firms) with a gross output of $2,000,000 and over, out of a sectorial total of 1,285 firms, accounted for $520,000,000, worth 60.4% of all industrial production. Presenting his 1979 report, President Hillis said, ‘manufactured products now account for between 25% and 30% of the country’s export receipts and virtually all consumer goods, as well as a growing proportion of intermediate and capital goods are now supplied from local manufacture.’

Main findings

Settler colonial states with domestic control of the economy and elites interested in local development could industrialize better in defiance of the imperial policy that frowned upon industrialization in colonies. Manufacturing emerged and expanded in territories with fewer political links with the metropole. However, even with this relative freedom from the metropole, the colonial state did not initiate policies favorable to developing secondary industries. It took the lobbying and activism of industrial elites to achieve a favorable industrial policy in the face of opposition from the state mining, agriculture, and merchant capital. The contestations between the different economic interests showed how the organized elite was critical in economic decisions and public policy. More importantly, the book overcomes a key weakness characterizing the history of industrialization in Zimbabwe: an overemphasis on the state’s role in charting the way for industrial expansion. Instead, it probes both the actions of the industrialists and other economic interest groups in pushing the trajectory of industrialization in colonial Zimbabwe.

References

Arrighi, G., ‘The Political Economy of Rhodesia’, New Left Review, 39, (1966).

Butler, L., ‘Industrialisation in Late Colonial Africa: A British Perspective’, Itinerario, 23(1999).

Mlambo, Alois et al., Zimbabwe: A History of Manufacturing, 1890–1995 (Harare: University of Zimbabwe Publications, 1997).

Pangeti, E.S., ‘The State and Manufacturing Industry: A Study of the State as Regulator and Entrepreneur in Zimbabwe’, (PhD, University of Zimbabwe, 1996).

Phimister, I., An Economic and Social History of Zimbabwe, 1890-1948: Capital Accumulation and Class Struggle (London: Longman, 1988).

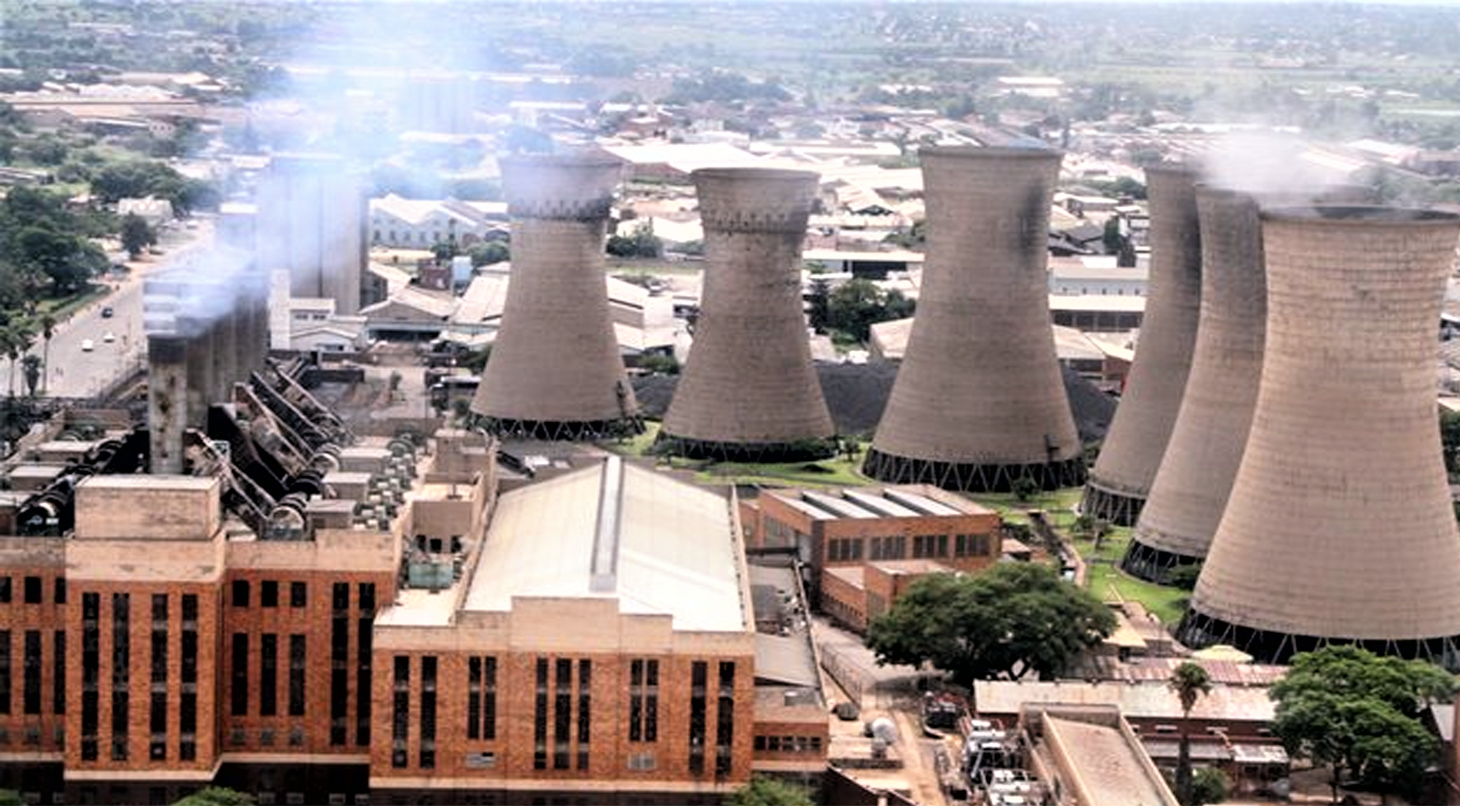

Feature image: A public/Getty image of the industrial area of the city of Bulawayo.