The field of African Economic History is flourishing. The rising number of participants at the annual meeting of the AEHN, the increasing flow of articles in mainstream economic history journals and thriving research groups in Lund, Wageningen and Stellenbosch, just to name some of the larger research clusters, testify to this. The ‘new economic history of Africa’ is strongly data driven, with researchers using published and unpublished sources to create datasets, establish and compare trends, and conduct statistical analysis to tease out causality (for discussion and an overview, see the recent paper by Johan Fourie (2016)

To further expand our empirical knowledge of long-term African development, the potential of colonial archives in Europe is hardly exhausted, with researchers using trade, tax, wage, price, climatological, and criminal statistics to make a wide range of new and compelling contributions. However, there is much scope to venture beyond Europe’s missionary and government archives, which tend to focus on key administrative matters and provide only limited information on the seemingly mundane and practical intricacies of colonial rule. Previously neglected, individual-level data sources have already shown to harbour great potential to advance our knowledge of long-term African development. Recent contributions have utilized sources preserved in archives on African soil, including military recruit records, the performance files of police officers, hospital registries, and the marriage records of Anglican Africans.

Archival documents in Uganda are in a state of flux after having been largely neglected or even destroyed during Uganda’s troubled post-colonial history. In recent years, things have been changing for the better. Social, cultural and political historians such as Derek Peterson (Michigan), Holly Hanson (Mount Holyoke) and Shane Doyle (Leeds) – just to name a few internationally renowned scholars – have been producing work that is firmly based on local source materials found in Uganda’s national, district and missionary archives.

Michiel de Haas and Felix Meier zu Selhausen share some of their experiences exploring a variety of source materials in Uganda. Michiel has been affiliated with the Makerere Institute of Social Research (MISR) in Kampala and visited the National Archives in Entebbe and five district archives. He has also conducted oral history interviews with cotton farmers in Eastern Uganda. Felix lived in Fort Portal for three years where he taught at Mountains of the Moon University. He has digitized marriage records from Anglican churches all over Uganda and in-patient registers from Western Uganda’s Kabarole Hospital.

Government Archives

Without any previous experience with research in Uganda, Michiel’s only source of information on its archival resources was an article by Barrett-Gaines & Khadiagala (2000). About the National Archives, this article remarked, “the trick is to get the staff to make available the total collection of catalogues, a task accomplished by being patient, cheerful, personable, polite, calm, and persistent.” With regard to regional archives, the authors warned, “where they exist, [their state] is dismal.” In Kabale district, for example, “the attic is an uncomfortable, dark, and dusty place to work. A small pocket flashlight and wet cloths are advisable.”

Michiel’s experience was very different. Professor Derek Peterson and a team from the University of Michigan have recently made a committed effort to catalogue the Ugandan National Archives, to completely reorganize and catalogue the District Archives in Jinja and Kabale, and to reorganize, catalogue and digitize several archival collections in Western Uganda. These are now safely harboured at the Centre for African Development Studies of Mountains of the Moon University (Fort Portal). The Michigan team have strived to both conserve, and increase the accessibility of the archives. Derek Peterson recently summarised the exciting possibilities of preservation and digitization at Mountains of the Moon University in a podcast inverview.

In the National Archives, which recently moved from Entebbe to a brand new location in Kampala, Michiel found detailed administration reports and correspondence between colonial officials, revealing information on controversial colonial practices, like forced labour and indirect rule, on which the British Archives provide far less insight. With the assistance of a friendly archive staff, Michiel worked through a large amount of material in only a week’s time. In the regional archives of Kabale and Jinja, Michiel was permitted to explore the archive on his own. This contrasts sharply with his experience in the Teso District Archive, which has not (yet) been reorganized. Although accessible with the help of a local research assistant, the archive was no more than a damp room with an impressive dump of randomly piled documents, with termites literally (and audibly) eating away at the precious heritage. Michiel noted that archivists tended to be rather protective of their collections, and that permission to take photographs should not be taken for granted. Photographs were allowed in all archives, but, in most cases, required active permission of the archivist, which was provided after reassurance that the photographs were for personal (professional) use, and would not be distributed further.

The Jinja District Archives before and after reconstruction by a team of students from the University of Michigan and local archivists. Although at the time of Michiel’s visit the archive was still suffering from flooding, the documents were neatly catalogued and safely preserved in boxes.

The Jinja District Archives before and after reconstruction by a team of students from the University of Michigan and local archivists. Although at the time of Michiel’s visit the archive was still suffering from flooding, the documents were neatly catalogued and safely preserved in boxes.

Michiel working through colonial archives in Soroti (Teso). During his visit in September 2015, the archive was no more than a large termite-infested pile of unsorted documents. Researchers had no other option but to find a (clean and dry) patch of grass in front of the archive to analyse and photograph the documents.

Michiel working through colonial archives in Soroti (Teso). During his visit in September 2015, the archive was no more than a large termite-infested pile of unsorted documents. Researchers had no other option but to find a (clean and dry) patch of grass in front of the archive to analyse and photograph the documents.

Preparation for an archival research trip is crucial. In the case of Uganda government archives, a research proposal must be submitted and permission obtained from Uganda’s National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST), a process that could only be set in motion by first affiliating with one of Uganda’s recognized universities or research institutes. Michiel affiliated with the Makerere Institute of Social Research (MISR), which also provided a lively and welcoming environment in which to establish relations with Uganda-based scholars. Note that MISR recently raised its affiliation fee from $300 to $1,000, but it is only one of many affiliation options. The process of acquiring the UNCST-permit remains slow and can only be completed upon arrival. However, Michiel managed to obtain the necessary official papers to gain archival access within a few days. Extremely helpful in the process was Michiel’s acquaintance with experienced international and local scholars who helped him to gain access and communicate with archivists.

Anglican Church Archives

Church archives across the world have been crucial in the reconstruction of historical demographic trends – the church being typically the earliest institution recording vital statistics of its members consistently over time. Church archives in Uganda (and elsewhere in Africa) reaching back to the late 19th century when Christian missionary societies arrived and ever since Christianity gradually grew into one of the most powerful cultural forces.

The general archive of the Anglican Church of Uganda (formerly known as Church Mission Society), is located at the Hamu Mukasa Library at Uganda Christian University (UCU) in Mukono. In recent years UCU in collaboration with Yale University Divinity School Library has embarked on a country-wide collection and cataloguing of parish church records, including correspondences, personal records and administrative documents that trace the development of the Church and its relationship with the Church of England and the British colonial government.

However, the vital registers of baptism and marriage of Ugandan converts are stored at the local parish level. Sarah Walters (LSHTM) and Shane Doyle, historical demographers of East Africa, photo-digitised and analysed some of the oldest Catholic parish registry in Buganda and Ankole. More recently, Felix uncovered the enormous potential of Anglican Church parish registers in Uganda for social and economic historical research. For him, the prime treasure in the Anglican parish archives are the marriage registers, which he first encountered in 2012 at St. John’s Cathedral in Fort Portal and Namirembe Cathedral in Kampala. Like the parish registry of the Catholic White Fathers, the Anglican Church Mission Society (CMS) recorded both names and ages of married couples, but Anglican registers also include detailed indications of literacy and occupations. For further data and fieldwork details see the Economic History of Christian Africa project website.

Astonishingly, despite rudimentary storage conditions (usually wooden cabinets), the hazards of fire and termites, and the general difficulties of record preservation in tropical climates, Felix observed during his fieldwork at 18 Anglican parishes across Uganda that most of the ecclesiastical records have stood the test of time. There is great variation in the data quality and availability between parishes and often one has to tempt ones fortune. However, Felix has observed that the Anglican archives in Uganda appear to be the best preserved in both East and West Africa. This does not mean the Ugandan registers are not in decay. In fact, many records are on the brink of becoming unreadable, demanding wider, more coordinated efforts to identify existing parish registers Uganda and safeguard them.

The poor state of the local parish archives has not escaped the attention of the Anglican Church. Consequently, the clergy did not request a fee from Felix for granting access to their registry, but typically welcomed – often enthusiastically – its digital preservation. In order to thank the church for their openness and help safeguard its heritage, Felix provided all the churches he visited with a digital copy of the preserved registers, which were stored on the Diocesan computer or on a USB-stick for the more rural parishes. The entire photo archive of 38,000 Anglican marriages is stored at the Centre for African Development Studies at Mountains of the Moon University, complementing their laudable efforts to preserve and catalogue the Toro kingdom and various district archives. These data are currently being processed into a database.

However, Felix warns that researchers cannot expect to be successful in simply wandering into churches and asking to see what are essentially the private documents of parishioners. While UNCST research clearance was not demanded by the Church, official introduction (letters) from a Ugandan university, an Anglican archive, local clergy or the Church of England is absolutely crucial in the establishment of researcher-church relations. Throughout the entire data-collection process for his PhD research, Felix benefitted tremendously from his affiliation with Mountains of the Moon University and letters of recommendation and phone calls made by the Anglican clergy who helped facilitate his fieldwork.

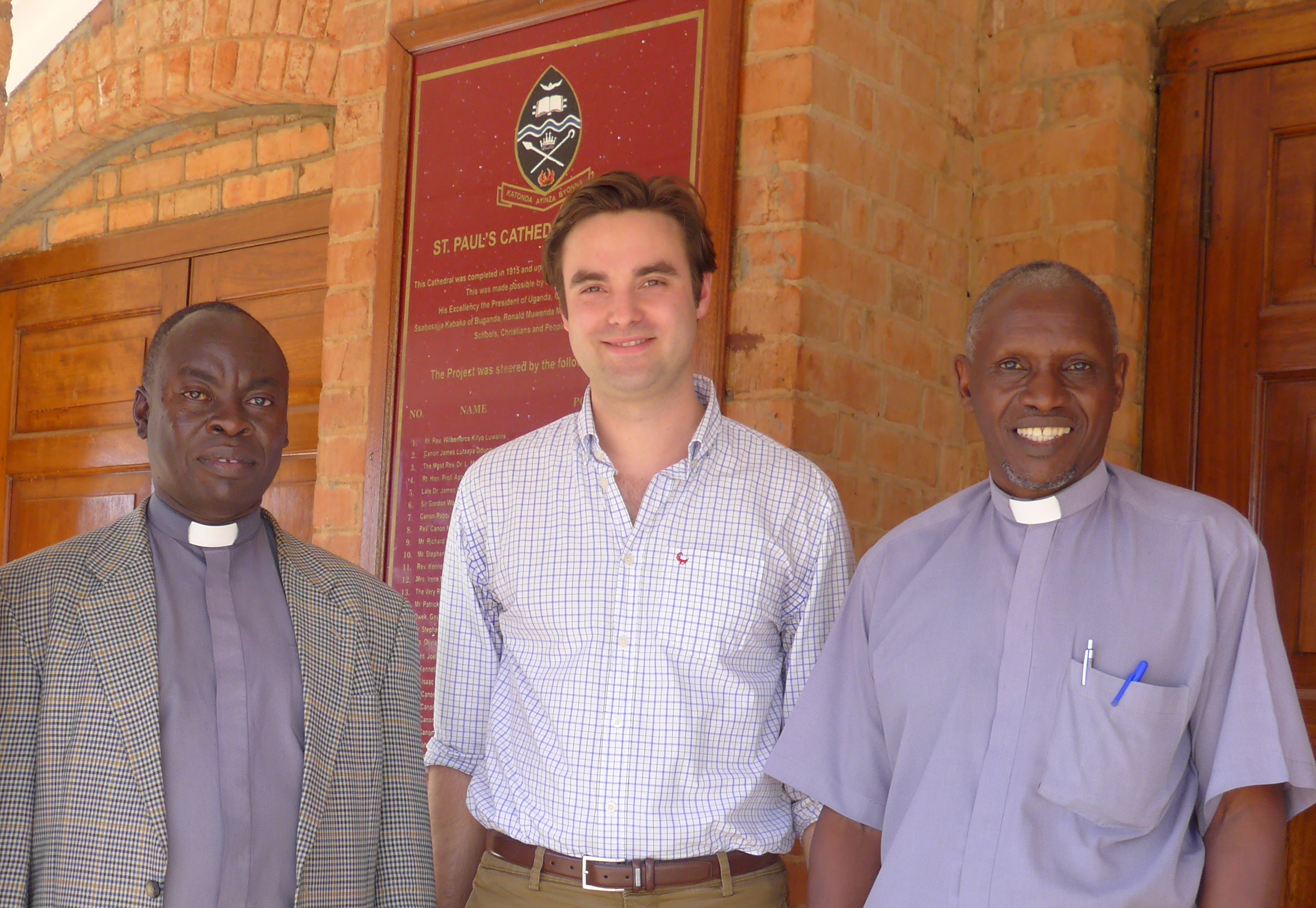

Felix in April 2014 at Namirembe Cathedral in Kampala with the local Vicar (left) and Provost Benon Kityo (right) during his many research visits to the Cathedral’s marriage archive which, among others, he fully digitally preserved (17,000 certificates), including the earliest ones found at Africana Section of Makerere University.

Felix in April 2014 at Namirembe Cathedral in Kampala with the local Vicar (left) and Provost Benon Kityo (right) during his many research visits to the Cathedral’s marriage archive which, among others, he fully digitally preserved (17,000 certificates), including the earliest ones found at Africana Section of Makerere University.

Finally, besides offering spiritual and educational services the Anglican Church also pioneered the provision of public health services in Uganda. Thus, if preserved, Anglican hospitals may retain patient registers dating back to the early colonial era. Felix explored the records of Toro Hospital (now Kabarole Hospital) in Fort Portal, the second oldest Anglican hospital in Uganda, founded in 1903. Indeed, the hospital preserved many of its colonial-era in-patient records, which cast important light on local diseases, medical advances and long-run health development in rural Uganda. However, it remains unclear how successful other hospitals have been in preserving their registries and whether researchers are permitted to view and digitise these ethically delicate sources. Offering to make historical patient names unreadable may increase chances of gaining access. However, making connections is key, and an introduction by the Church to the hospital administration may open doors for researchers.

AEHN members and other economic historians are engaging in numerous ongoing research activities across Africa. The experiences shared by Michiel and Felix provides insight into some of the current research prospects in Uganda. We hope that this type of communication helps foster accessibility, and we kindly invite readers to share their own experience of doing economic history in Africa in the comments below and future blog posts.

References

Barrett-Gaines, Kathryn & Lynn Khadiagala (2000), “Finding what you need in Uganda’s archives”, History in Africa, 27, pp. 455-470.

Fourie, Johan (2016), “The Data Revolution in African Economic History”, Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 47(2), pp. 193-212.

The Frontiers editorial team consists of Michiel de Haas, Kate Frederick (both Wageningen University) and Felix Meier zu Selhausen (University of Southern Denmark & University of Sussex). AEHN board members Ewout Frankema (Wageningen University) and Morten Jerven (Norwegian University of Life Sciences) form the supervisory board.

We welcome external contributions to the blog and encourage those interested to submit a summary of a recent working or published paper or book review, a commentary on current African developments or something else. Please contact the editors to discuss possible posts at [email protected].

Dear colleagues, thanks for this interesting post. We could argue that similar events occurred in a number of countries in Africa. In the case of Senegal, we found evidences of lack of ressources to protect the documentary sources. If these files are not well conserved, the impact on research and historical knowledge are hardly affected. For instance, the National Archives of Senegal (re-opened this year) were closed since 2014 and Ph.D candidates were not able to develop their researches. On the other hand, despite the re-ouverture of the National Archives, there are a number of sections that remains in a poor state of conservation. In the case of Economic-Maritime historians like me, we must work in the “section P” that actually is a chaos. The staff that works in the “section P” are not able to organize the huge quantity of papers. Thus, as we could see in the photo (Facebook post), the situation is completely complicated. However, these sources are rich and provides complete data on port activity and other topics rarely published (I will expose some related topics in the next AEHN conference). So, the opportunities for the local-regional historians are great and financial efforts could be made in order to value this legacy not for international scholars but primarily for the African people and future generations. Best wishes from the Canary Islands.