Colonizer Identity and Free Trade in Africa

It has often been claimed that the structure of export trade between Africa and Europe during the colonial period depended on the colonizer’s identity, with the British favoring free trade and the French, in contrast, making greater use of their political power to establish trade monopsonies and acquire African goods at prices lower than in the world markets (Duignan and Gann 1975, pp. 8-9). Yet, the situation on the ground might have been quite different from what formal policies envisaged. Indeed, even in the British colonies, trading companies with de facto market power had been operating since the nineteenth century, even though discriminatory tariffs and official monopsonies were only introduced in the 1930s (Austin 2010, p. 15; Rönnbäck and Broberg 2019, pp. 179-80).

Whether producers in the British colonies enjoyed the benefits of free trade more than those in the French territories is thus an empirical question. Was the market power of trading firms operating under the two colonial powers different? Did producers in British colonies benefit from higher competition among trading companies by receiving higher prices than those in French colonies?

Estimating colonial trading companies’ profit margins

To answer these questions, in this paper, I measure the degree of trade competitiveness under the two colonial powers by computing profit margins for trading companies operating in British and French African colonies. Profit margins are estimated as the difference between European import prices and African export prices, net of trading costs. I use prices for various agricultural commodities exported between 1898 and 1939 (Frankema, Woltjer, and Williamson 2018; Tadei 2020) and estimate trade costs from Africa to Europe. The rationale behind this methodology is simple: with free trade, the profit margins of trading companies should be close to zero.

Colonizer identity or local conditions?

Having constructed profit estimates, I test whether the extent of the market power of trading companies was determined by the identity of the colonizer, with the British favoring free trade policies more than the French, or whether it was determined by other factors, such as local conditions in the colonies, which might have facilitated or prevented the establishment of monopsonies.

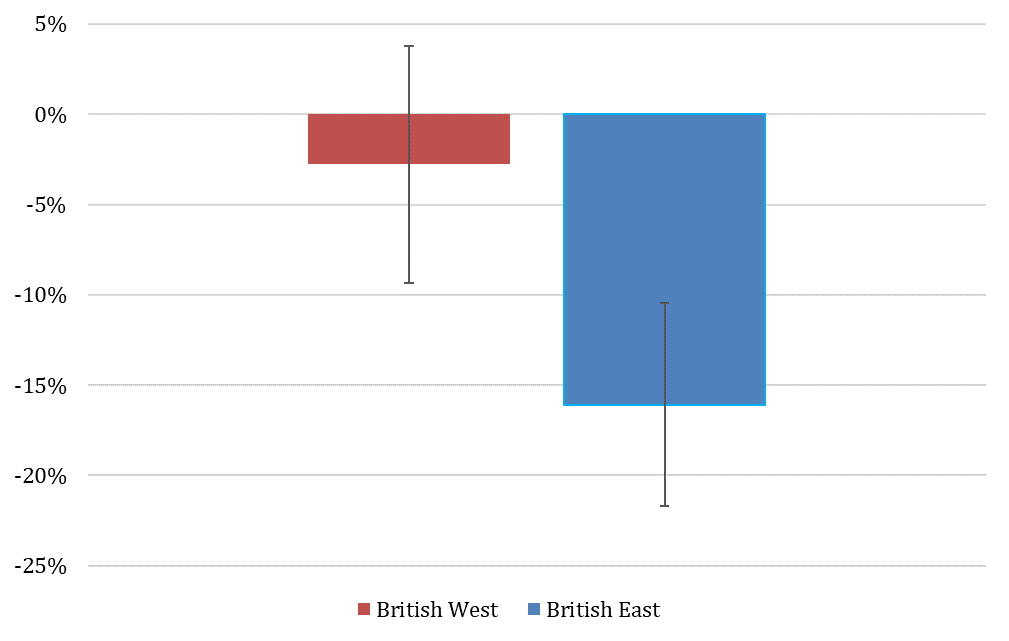

The results show that, on average, profit margins in the British colonies were lower than in the French colonies. However, if we compare the two colonial powers within one same region (West or East Africa), this difference disappears. Profit margins were statistically indistinguishable from zero in British East Africa, suggesting free trade, but equally large in both British and French West Africa, highlighting that West African colonies experienced substantial monopsonies both under the British and under the French (see figure 2). This suggests that actual extent of free trade depended more on the conditions in the colonies than on colonizers’ formal policies.

Figure 1: Average Difference with French West Africa Profit Margins and 95% Confidence Intervals

The East-West Africa Difference

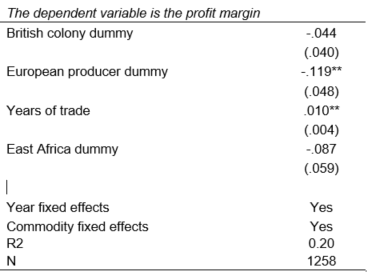

Why were profit margins lower in East Africa than in the Western colonies? To explore this question, I investigate how the implementation of monopsonies was affected by the history of trade relationships between Africa and Europe and the type of producers. In West Africa, the long history of trade and the higher level of commercialization reduced the operational costs of monopsonistic trading companies. At the same time, most agricultural production came from small African farmers with little political power and ability to oppose the establishment of monopsonies. In contrast, in East Africa, the modes of production were more heterogeneous, with European settlers and plantation companies playing a more significant role than in the Western colonies. When agricultural production was in the hands of Europeans, who had much greater political influence on the colonial and metropolitan government, the cost of enforcing monopsonistic practices increased, reducing profit margins. Indeed, as shown in table 1, when we control for the history of trade and the presence of European producers, the difference between profit margins in East and West Africa disappears.

Table 1: Explaining the Lower East African Profit Margins: Shorter History of Trade and More European Producers

Conclusions

Overall, the results challenge the view of the British colonizers as champions of free trade. Besides formal policies, other factors were at play in determining the actual extent of free trade in the African colonies. Profit margins were influenced primarily by the local conditions in Africa (history of trade and presence of European producers), rather than by the identity of the colonial power.

References

Austin, G., ‘African economic development and colonial legacies,’ International Development Policy, 1 (2010), pp. 11-32.

Duignan, P. and Gann, L. H., ‘Introduction’, in Duignan, P. and Gann, L. H., ed., Colonialism in Africa, 1870-1960, vol 4 ‘The Economics of colonialism’, pp. 1-32 (Boston, 1975).

Frankema, E., Woltjer, P. and Williamson, J., ‘An economic rationale for the West African scramble? The commercial transition and the commodity price boom of 1835–1885’, Journal of Economic History, 78 (2018), pp. 231-267.

Rönnbäck K. and Broberg O., Capital and colonialism: the return on British investments in Africa 1869–1969 (Cham, 2019).

Tadei, F., ‘Measuring extractive institutions: colonial trade and price gaps in French Africa,’ European Review of Economic History 24 (2020), pp. 1-23.

Tadei, F., “Colonizer Identity and Trade in Africa: Were the British More Favourable to Free Trade?“, Economic History Review, 2021, forthcoming.

Featured image: United Africa Company Steamship SS Zarian.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:SS_Zarian.jpg