Polygyny, the practice of a man marrying more than one woman, is a common practice in many parts of the world, particularly in the African “polygyny belt”, stretching from Senegal to Tanzania, where between a third and a half of married women are in a polygynous union. The practice of polygyny, however, decreased significantly in the past century (Fenske 2015). This decrease is arguably one of the most significant transformation of marriage practices around the world. Did the expansion of primary education in the 20th century play a role in the decrease of polygyny? In 1950, less than a third of primary school age children were attending school in Sub-Saharan Africa. Today, the figure is close to 80%. In a recent paper (André and Dupraz 2023), we focus on Cameroon, a Central-African country that experienced a major expansion of primary education during its late-colonial period. We investigate whether the education received by young people during this period influenced their marital choices.

Why would education matter for polygyny?

Education can directly influence polygyny by changing cultural norms. In Africa during the colonial period, Christian missions and colonial governments provided formal education. The role of Christian missions in fighting polygyny in Africa has been studied extensively (Becker 2022, for a recent paper). We focus on public, nonreligious education. Colonial governments also viewed marrying only one person (monogamy) as a better marital custom, but were less opposed to polygyny than Christian missions, in part to ensure the cooperation of local elites (Walker-Said 2018). Unlike Christian schools, it seems that public schools did not actively discourage polygyny. For this reason, in our study, we differentiate between public and private education, which likely had different effects on polygyny.

Education can also impact polygyny by empowering women. Educated women have more opportunities to work and earn money, which means they are less reliant on marriage for financial security. This increased economic independence can also give them more power in deciding whom to marry. Women with more bargaining power may be more likely to choose a monogamous marriage and may also be able to prevent their husband from taking a second wife.

Finally, education can affect polygyny through what economists call “marriage-market returns to education”. Education can make people more desirable on the marriage market. For men, this could mean being able to marry more than one wife. For women, this is more complicated. If educated women are more desirable, they may find it easier to marry monogamously if this is what they prefer. But women (and their families, also involved in marriage decisions) may value both monogamy and other traits associated with a polygynous husband, such as wealth or social status.

Late colonial expansion of education in Cameroon

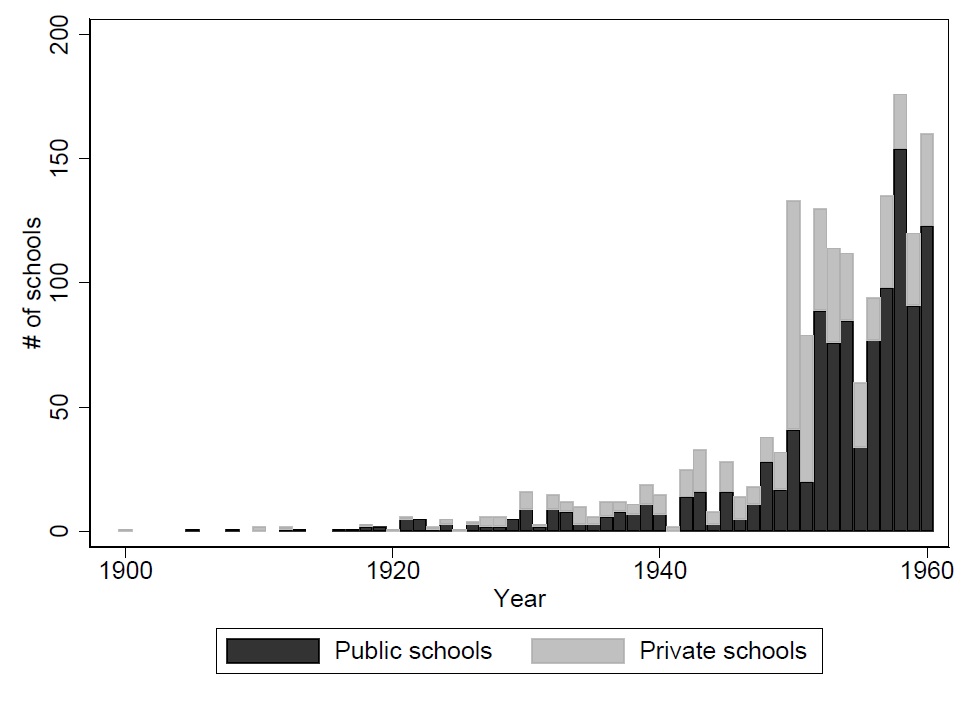

After World War II, public expenditure on primary education exploded in both French and British Cameroon (the two parts were reunited at independence). Colonial governments increased subsidies to missionary schools and built more public schools. Figure 1 displays the historical evolution of the flow of school openings between 1900 and 1960. The change in the late colonial period is clearly visible.

Figure 1. Flow of School Openings in Cameroon 1900-1960

Note: the bars representing private schools are stacked on the bars representing public schools so that the graph shows the total number of schools. Source: 2016 administrative data on the universe of Cameroonian schools with the date of construction (see André and Dupraz 2023 for a discussion).

Women who received more public education were more likely to be in a polygynous union, as first wives

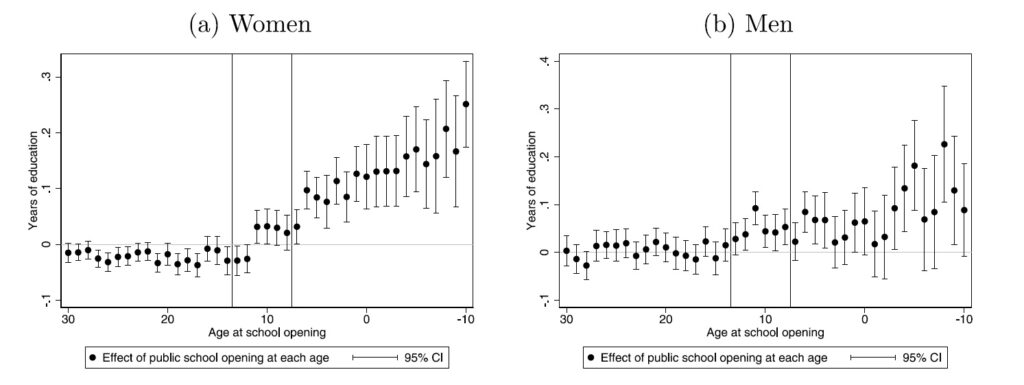

To estimate the causal effect of education on polygyny, we use administrative data on Cameroonian schools, with their location and date of opening, and 1976 population census data. For all individuals in the census, we know the number of schools and school openings in their village at every date. We study how education and marriage practices evolved over time in villages where many schools were built versus villages were few or no schools were built. More precisely, we regress an individual’s education on the number of school openings at every age, controlling for village and year of birth fixed effects (and other controls detailed in the paper). Figure 2 plots the coefficients of this regression, for men and for women. Schools opening in the village before an individual was of school age are associated with more years of education, but reassuringly, schools opening in the late teens and adulthood have no effect on years of education.

Figure 2. Event-Study Graphs: Effect of School Openings on Education

Note: both figures display the coefficients of a regression of an individual’s years of schooling on the number of public and private school openings in their village at each age, along with village and cohort fixed effects and other controls. Only the coefficients on public school openings are shown on these graphs, for readability. The regressions for men and women are run separately.

In a more compact version of this exercise, we regress education and marriage market outcomes on the number of public and private schools in the village when an individual was a child of school entry age (we also include village and cohort fixed effects and other controls detailed in the paper). Table 1 shows that one additional public school in the village when a woman was a child increases her education by 0.083 years and the number of spouses of her husband by 0.018. Together, these figures imply that one year of education increases the number of co-spouses by 0.22. Education also increases the number of spouses of men. (Interestingly, private schools decrease the number of co-wives of women, but results are hard to interpret because, unlike public schools, private schools were built in villages where polygyny was already declining). When we look at the rank of women in the marriage, we find that education increases the likelihood to be in a polygynous union as a first wife, but not as a second and third wife. First wives in polygynous unions typically enjoy greater status and bargaining power than second or third wives.

Table 1. First Stage and Reduced Form for Married Men and Women

|

Women |

Men |

|||

| Years of Education | No. of Co-Wives | Years of Education | No. of Co-Wives | |

| No. of public schools at school entry age | 0.0825*** (0.0096) |

0.0180*** (0.0069) |

0.0483*** (0.0098) |

0.0091*** (0.0029) |

| No. of private schools at school entry age | 0.0942*** (0.0168) |

−0.0301*** (0.0087) |

0.0749*** (0.0180) |

0.0103** (0.0048) |

| Observations | 490,045 | 490,045 | 470,247 | 470,247 |

Note : Sample : all non-migrant married women ages 25-60 in 1976. Standard errors clustered at the village level in parentheses. *p<0.01; **p<0.05, ***p<0.01. school entry age is 7 for women and 13 for men (there is more late school entry for men). All regressions control for village and cohort fixed effects, cohort fixed effects interacted with a dummy equal to 1 in British Cameroon, and a vector of time invariant village controls interacted with a cohort quartic trend.

Educated women married educated men, more likely to be polygynous

It is hard to believe that going to public school increased Cameroonian women’s preference for polygynous men, all things being equal. However, men who ended up having multiple wives came from wealthier families, had more education, and better job prospects. It is not hard to believe that these traits were highly valued by women and their families, especially in a period when labor-market opportunities for educated women were limited. In late colonial Cameroon, as in a lot of countries today, there was strong “assortative matching on education”, meaning more-educated men and women tended to marry each other. In the paper, we show that this explained why secular education made women more likely to marry a polygynous man. Educated women married educated men, and these educated men were more likely to become polygynous. Using a structural model of marriage, we show that accounting for assortative matching on education is enough to explain why educated women married polygynous men as first wives.

References

Becker, Bastian, 2022. The colonial struggle over polygamy: Consequence for educational expansion in sub-Saharan Africa. Economic History of Developing Regions 37 (1), 27–49.

Fenske, James , 2015. African polygamy: Past and present. Journal of Development Economics 117, 58–73.

Walker-Said, Charlotte, 2018. Faith, Power, and Family: Christianity and Social Change in French Cameroon. James Currey, Oxford.

Feature image: Students of the primary school and kindergarten of Hikoadjom in front of the oldest building of the school. Source: Wikimedia.