During the colonial period, European powers established various coercive economic institutions in their African territories. These included monopolies and monopsonies on trade, price controls, taxation, and forced labour. It is widely recognized that such institutions were primarily extractive and likely hindered long-term development.

Despite this consensus, there is little systematic, quantitative evidence on the exact rates of extraction imposed by these institutions or their micro-economic impacts. A notable exception is the work of Tadei (2020), who found that peasant agricultural producers in French West and Central Africa received prices 20-40% below market rates.

In a recent study, we focus on one of the more notorious colonial practices: forced wage labor (FWL), which was particularly widespread and persistent in Portuguese Africa. Using archival records from the Sena Sugar Estates (SSE)—for a long period the largest private employer in colonial Mozambique—we analyze the extent of labour extraction and its impact on the firm’s profitability from 1920 to 1975.

Labour Coercion in Colonial Mozambique

In Portuguese Africa, forced wage labour was codified in law as early as 1878, imposing a “moral obligation” on indigenous men to work. Though some freedom to choose employers existed on paper, in practice, labour supply and allocation were heavily controlled by the state. For example, under the 1921 ‘Hornung Contract,’ colonial authorities in Mozambique committed to supplying 3,000 labourers to the Sena Sugar Estates every six months for 20 years. To meet these quotas, men were forcibly taken from areas as far as a three-week march from the plantations.

Consistent data on the magnitude of forced labour is scarce. However, scattered observations suggest a steady increase in the number of men conscripted. In the Manica and Sofala districts, the number of men mobilized for work rose from 25,000 after World War I to over 100,000 by the late 1920s. From World War II until the late 1950s, nearly the entire eligible male population was conscripted for forced labour. In the neighboring Zambézia district, the proportion of adult males mobilized for work grew from 34% in 1928 to over 90% by the late 1940s and 1950s.

Estimating Rates of Extraction

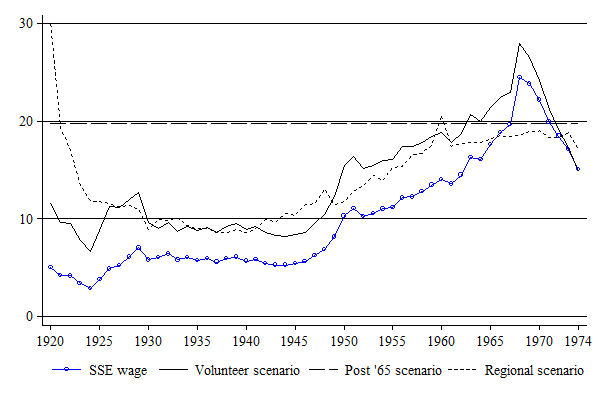

In our study of SSE, we estimate the rate of extraction associated with FWL by comparing the wages of coerced ‘native’ workers to plausible free-market wage alternatives. Data on wages paid to native workers is available from historical firm records, but as labour coercion was widespread finding a counterfactual wage is more complex. We approximate free-market wages using three methods: (1) wages paid to volunteer workers at SSE who were outside the forced labour contract system, (2) wages paid to African workers at SSE after 1965, when a freer labour market emerged, and (3) wages from nearby regions where labour coercion was less severe.

As shown in Figure 1, this exercise reveals that SSE wages were consistently lower than all three of the counterfactuals. On average, we estimate that native workers received about 40% less than they would have in a freer market. Over time, however, extraction rates did decline, coming close to zero by the end of colonial rule in 1975.

Figure 1. Total remuneration of native workers at SSE, actual and counterfactual, in decimalized pence

Notes: The solid blue line shows the total mean daily remuneration of native workers at SSE, comprising wages, food, and lodging; the remaining lines show daily remuneration under the three counterfactual scenarios. All values are stated in constant 1950 prices.

Source: Jones and Gibbon (2024).

Did Coercion Boost Profitability?

A follow-up question is whether forced labour increased firm profitability. If wages were higher, and all else remained constant, profitability would certainly decline. From this very simple accounting perspective, our analysis suggests that SSE’s return on capital would have been at least three percentage points lower—and sometimes negative—without access to forced labour.

However, evidence from various contexts suggests that coercion has negative consequences for productivity. Forced labour often led to increased worker illness and reduced effort. Evidence from SSE set out in the paper supports this view, suggesting that higher wages (i.e., less coercion) may have been offset by productivity gains. Thus, we conclude that the firm could have remained profitable, although perhaps at a moderately lower level, without relying on labour coercion for most of the period.

Implications

Despite claims during the period, the evidence from SSE suggests that the pure economic case justifying the use of forced wage labour was ambiguous, especially in the later years of colonialism. While it reduced local labour costs and ensured a steady labour supply, it likely hampered productivity, meaning firms like SSE did not enjoy super profits compared to UK-based companies generally. Furthermore, by upholding a racially segregated economic system and neglecting investment in African human capital, extractive institutions such as FWL very likely hindered the post-colonial transition to economic independence.

References

Tadei, F. (2020). Measuring extractive institutions. Colonial trade and price gaps in French Africa. European Review of Economic History, 24, pp. 1-23.

Feature image: Sena Sugar Estates locomotive next to the processing plant in Luabo, 1969. Source: https://delagoabayworld.wordpress.com/

Sena Sugar Estates used forced labour to assure production and this was wholly unacceptable, but efforts were made towards integrating the work force into management roles in the 1970s by my father, Stephen Hornung. It was difficult and it was not a success.

Super profits were made by my great grandfather from 1914 to 1920, when the Sena Sugar Factories produced and sold 187,412 tons of raw sugar which had climbed from £9 per ton in 1914 to £95 per ton in 1920.

Pitt Hornung’s share of the profits was £2million, about £100 million today. This money was used to build a new factory in Luabo and to expand the plantations.