Labour scarcity and coercion

In a recent discussion of her book Africonomics, Bronwen Everill highlighted the tensions between European settlers and Africa’s indigenous populations, rooted in a fundamental misunderstanding of Africa’s factor endowments. Settlers, coming from labour-abundant, land-scarce regions, encountered a contrasting African environment where labour was scarce and land abundant (Everill, 2024). This reversal placed a premium on labour costs and created cognitive barriers to understanding economic behaviour. Settlers’ preconceived notions about African labour markets were shaped by their European experiences. As Everill explains, “these ‘preconceived ideas’ included the assumption that ‘unskilled labour’ should be cheap [in Africa] because in Britain or in France or in the Netherlands or in Germany, it is cheap” (Fourie & Schoots, 2024).

Such misconceptions had far-reaching consequences. To rationalize the perceived unwillingness of African workers to accept low wages, European settlers and administrators often turned to racial assumptions, which informed policies aimed at artificially reducing labour costs (Mosley, 1980). These policies included enclosures and land grabs, perhaps best exemplified by South Africa’s 1913 Natives Land Act, which prevented Black South Africans from owning 90% of the land. These interventions were tools to coerce African workers into a labour force that sought to extract their productivity at minimal cost.

My recent paper shows that, like European settlers, colonial concession companies in the 19th and early 20th centuries had similar assumptions about African labour’s responsiveness to low wages. This was especially true in extractive industries, where large-scale production and unpredictable mineral discoveries forced firms to operate in remote areas, amplifying their monopsonistic control over regional labour markets. This control widened the gap between workers’ reservation wages and the wages employers were willing to offer, prompting firms to adopt arguably even more coercive recruitment methods. Unlike settler colonies’ land restrictions, concession companies often turned to direct forced labour to meet operational needs.

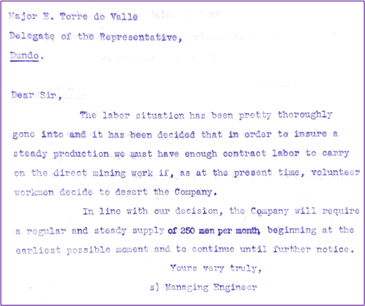

The coercive environment of the Portuguese colonial empire, especially the Indigenato system, compelled native populations to work under both ‘moral and legal’ obligations, fostering exploitative labour practices (Jerónimo, 2015). For example, a Diamang memo shows how management, facing a shortage of local labour and high worker mortality, resorted to forced labour for the most dangerous roles in diamond mining.

Figure 1. Memo from Diamang to Angolan Colonial Government (1926), requesting an indefinite supply of forced African labour

Note: The engineer’s name has been intentionally redacted.

Diamang: persistence and change

Diamang’s reliance on coercive labour was deeply embedded within the economic and political structures of Portuguese colonialism. For decades, the company operated a dual labour system: voluntary workers handled lighter tasks, while forcefully conscripted labourers undertook hazardous jobs such as blasting and excavation. Portugal’s economic dependency on Diamang’s revenues, coupled with the company’s monopsonistic control over its regional labour market, sustained this system. This created a self-reinforcing cycle where coercion was both profitable and institutionally normalized.

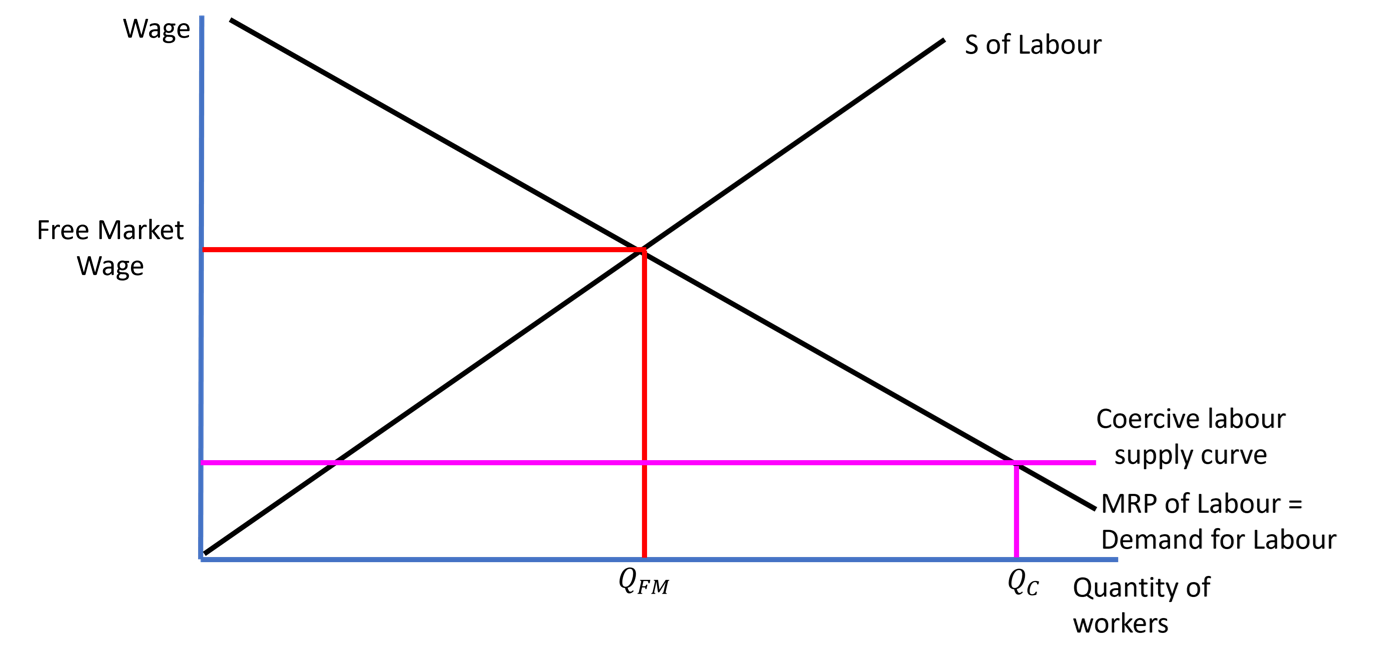

To understand why coercive labour systems persisted, my research applies an economic model extending existing theories of monopsony and labour coercion (Naidu 2020; Rönnbäck 2024). As the sole and dominant employer of labour, Diamang faced severe diminishing returns when trying to attract additional voluntary workers. The highly inelastic labour supply curve meant that significantly higher wages would be required to create a large voluntary workforce (Figure 2). As such, forced labour offered a highly cost-effective alternative, as its marginal cost remained constant regardless of the number of workers employed. This economic calculus entrenched forced labour as a preferred strategy, enabling Diamang to maintain production levels without incurring the escalating wage costs typical in a free labour market.

Figure 2. A monopsonistic employer facing a highly inelastic labour supply and a coercive channel to forcefully recruit labour

Note: MRP = Marginal Revenue Product of labour.

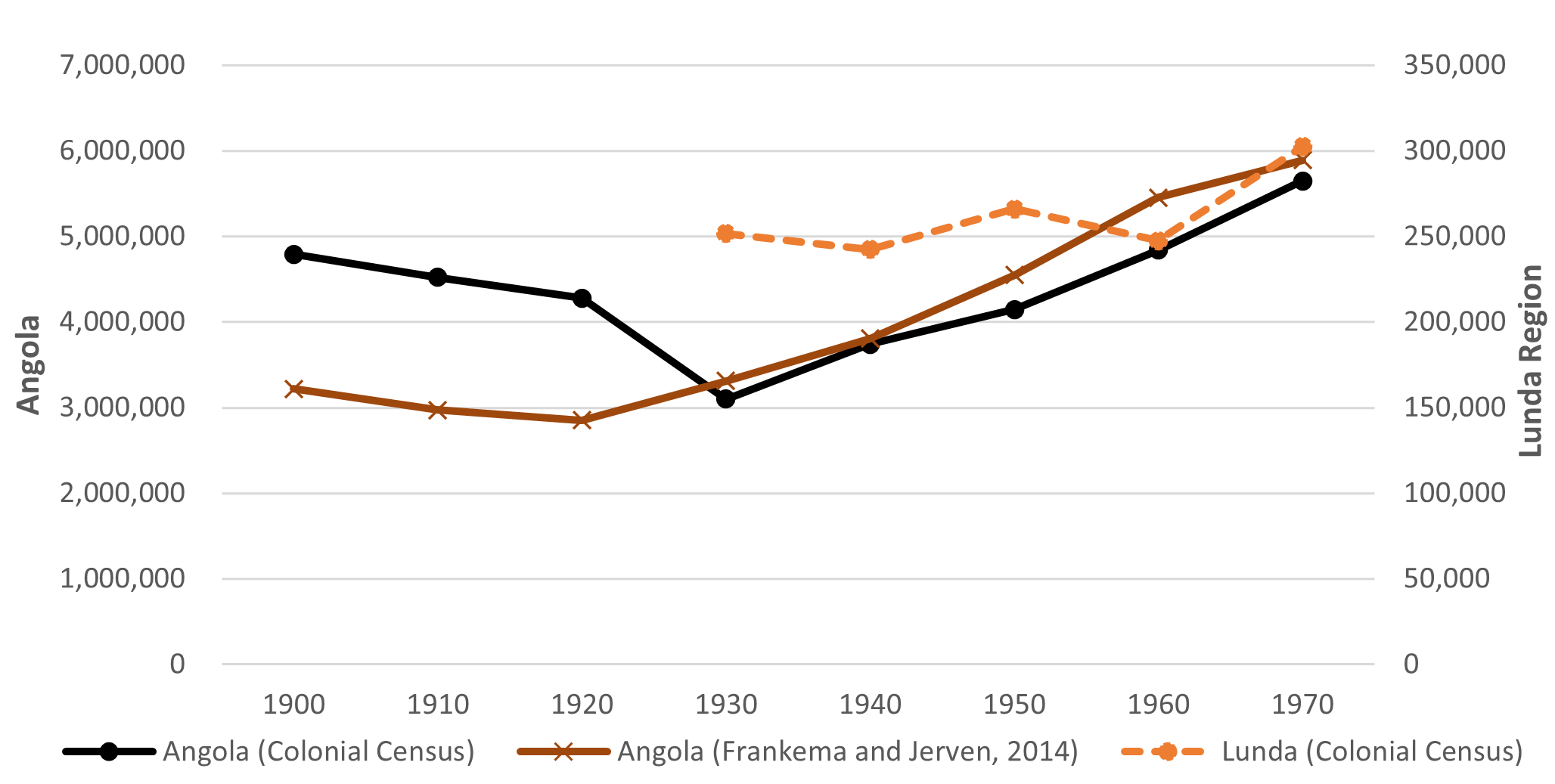

Compared to other European colonizers, Portugal was slow to reform its forced labour policies, resisting international pressure to abolish such practices even after the Second World War. This reluctance allowed Diamang to institutionalize coercion as a normalized business strategy throughout much of the 20th century. Furthermore, labour scarcity persisted into the 1960s, exacerbated by emigration to the bordering Belgian Congo to escape forced labour. As a result, the population in Lunda, the region where Diamang operated, stagnated, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Population of Angola and the Lunda Region, 1900–1970

Source: national census data were sourced from the Central Department of General Statistics (1933–1973) through their Statistical Yearbook. Population for Angola from Frankema and Jerven (2014).

Catalysts for transformation

However, beginning in 1961, a period of profound transformation began. The company abandoned its reliance on forced labour and moved toward a more market-oriented approach in response to external and domestic pressures, which improved worker conditions and wages. With Congolese independence in 1960, Diamang began to improve wages and working conditions to prevent a loss of workers to the newly independent Congo. In 1961, unrest in Angola, such as the Baixa de Cassanje revolt, led the colonial government to pressure companies to end forced labour. That same year, Ghana lodged a complaint with the ILO that exposed labour abuses, which renewed international scrutiny and reinforcing the need for reforms. The transition of Diamang to non-forced labour practices illustrates how entrenched systems can collapse under converging social and political pressures.

Conclusion

This research examines how Africa’s factor endowments and deeply rooted coercive labour systems within the Portuguese African empire shaped the practices of concession companies like Diamang. By introducing an economic model to show how indigenous labour markets and the institutional environment influenced Diamang’s operations, it explains why forced labour became so deeply ingrained within this company. Although this paper focuses on one firm, Diamang serves as a microcosm—albeit an exceptional one due to its size—of many concession companies within the Portuguese colonial empire. Post 1961, however, external pressures, regional instability, and international scrutiny compelled Diamang to abandon coercive labour practices in favour of more market-oriented policies. This shift, as shown in my other recent paper, significantly improved living standards, bringing them closer to those observed at other mining sites in Africa (Dolan, 2025).

References

Colony of Angola, Central Department of General Statistics Statistical Yearbook. (1933-1973). Luanda: National Press

Dolan, L. (2025). Living standards and forced labour: A comparative study of colonial Africa, 1918–74. The Economic History Review, (Forthcoming).

Everill, Bronwen. 2024. Africonomics: a history of Western ignorance. William Collins

Fourie, Johan, and Schoots, Jonathan. (Hosts). (2024, January 10). ‘Are good intentions bad? [Audio podcast episode]. Guest: B. Everill’. Our Long Walk. https://www.ourlongwalk.com/p/are-good-intentions-bad

Frankema, Ewout. 2021. ‘Why Africa is not that poor.’ In The handbook of historical economics, Academic Press, pp. 557-584.

Frankema, Ewout., and Jerven, Morten. (2014). ‘Writing history backwards or sideways: towards a consensus on African population, 1850–2010’. The Economic History Review, 67(4), 907-931.

Jerónimo, Miguel Bandeira. 2015. The ‘Civilising Mission’ of Portuguese Colonialism, 1870-1930. Springer.

Naidu, Suresh. 2020. ‘American slavery and labour market power’, Economic History of Developing Regions, 35 (1): 3–22.

Mosley, Paul. The Settler Economies: Studies in the Economic History of Kenya and Southern Rhodesia 1900–1963. .African Studies, Series Number 35. Cambridge University Press.

Rönnbäck, Klas. 2024. ‘Free or enslaved labour: a theoretical comparative model’, Journal of Global Slavery, 9 (3), 303-335.

Feature image: Medical inspection at Diamang.