African stock exchanges

Despite the continued resurgence in African economic history, the output of business and corporate historiography on Africa’s financial infrastructure lags considerably behind the actual contribution of the financial sector to the continent’s formal economy. Since 1960 more than 25 new stock exchanges have been established in Africa, showing governments’ motivation (and increasing urgency) to attract local, regional and global financial capital to an improving investment environment. With the lowest domestic savings and investments in the world, the capitalization of African stock exchanges might still be marginal to the global economy, but provides a strong testament to the future of the global economic system and the continent’s position in it (Moss 2008). Just as the current wave of financial globalization in Africa is connecting international capital to a growing pool of investment opportunities, the history of stock exchanges in Africa offers important insights into the development and organisation of financial markets in colonial and post-colonial economies.

Towards a history of Stock Exchanges in Southern Africa

The development of stock exchanges on the African continent in the second half of the 19th century coincided with the first age of financial globalization and European colonization south of the Sahara. Although securities were traded at informal markets in coastal areas of the continent much earlier, the first regulated stock exchange was the Kimberley Stock Exchange that operated during the Cape Colony’s diamond boom between 1880 and 1892 with nearly 60 registered members (Rosenthal 1968). British colonial influence ensured that initially shareholding, and later stock trading, became an integral aspect of settler economies and their ability to raise capital in the metropole (Accominotti, Flandreau, & Rezzik, 2011).

The mineral discoveries in South Africa’s Witwatersrand region in the early 1880s, with Johannesburg at the centre of the new gold rush, transformed the ZAR from a small agricultural economy into a settler colony on the brink of industrialisation. Although the ZAR was not the first territory in southern Africa where stocks were traded, the gold rush laid the economic foundations for the emergence of Johannesburg as the most important financial centre in sub-Saharan Africa. Joint-stock companies became a significant vehicle for combining wealth and spreading risk in the ZAR’s young mining sector. Founded on 8 November 1887, the JSE quickly enhanced the exceptionalism of South Africa’s early financial history, creating an alternative capital market to London (Rönnbäck & Broberg 2018) and other operating exchanges in the Cape Colony, Natal and the ZAR (Lukasiewicz 2017). The growth in gold production, the internationalization of the sale and demand for South African gold shares, and the convergence of interest rates in the European capital markets where the South African shares were traded make the JSE an appropriate case study of frontier capitalism during the first age of financial globalization.

From informal stock market to formal exchange

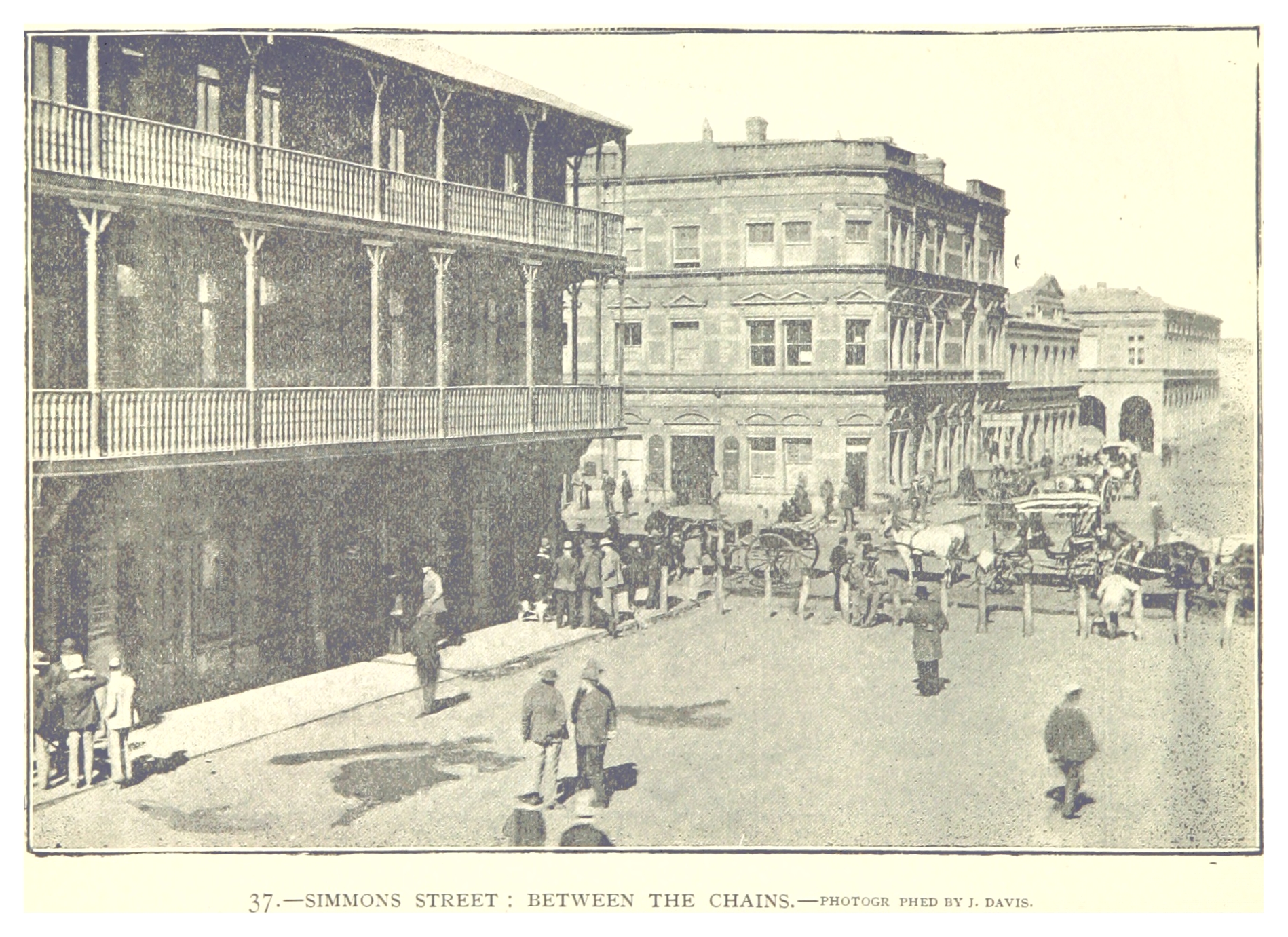

Just as in most global financial centers, trade in stocks in Johannesburg preceded the official opening of the stock exchange. Unregulated trading in shares and banking equity had already taken place in the small mining camp since 1886. The original owner and proprietor of the JSE, the Johannesburg Exchange & Chambers Company (JECC) was founded in late 1887 by the London-born and Kimberley-trained mining speculator, Benjamin Woollan, but was only formally registered in the ZAR on 28 February 1888. After the opening of the JSE, share trade in Simmonds Street was so great that in order to protect the speculators from oncoming traffic, Johannesburg’s first mining commissioner, Carl von Brandis, blocked off the section of the street entirely for share dealing with thick iron chains. The area that came to be knows as Between the Chains was seen as an extension of the JSE and not a separate market posing a threat to the trade inside the Exchange Hall (see Figure 1). Street trading in shares and land would continue beyond the operating hours of the JSE, turning it into Johannesburg’s hub of financial and social activity.

Figure 1: The Johannesburg Stock Exchange in 1893

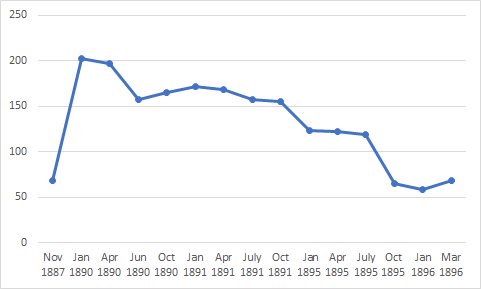

The simple, largely non-bureaucratic and non-restricting nature of the early Exchange promoted an early wave of registrations, expanding the number of shares on the Official List to more than 200 companies by the end of January 1890 (see Figure 2). This figure stabilized at around 150 listed companies after the development of deep-level mining from 1891 and dropped to just above 50 in the aftermath of the political and economic crisis caused by the Jameson Raid in early 1896.

Figure 2: Shares on JSE ‘s Official List

Source: ‘The Stock Exchange.’ The Star. 1887-1896

Organisational Structure

Although the basic structure of the JSE’s corporate organisation resembled the LSE in many ways and principles, the early JSE pioneers did not intend to replicate London’s stock exchange system in an understandably very different financial climate. Unlike in London, where the powers of the proprietors were already separated from the powers of the subscribers in the early 1830s, the development of the JSE was guided by the rivalry for influence over governance between the General Committee and the JSE’s landlords, the Johannesburg Estate Company. The division between ownership and operation, facilitated the emergence of the JSE’s regulatory sub-committees, investigating disputes and controversies over the rights and obligations of members. Woollan’s JECC was the owner, operator and regulator of the JSE until the formal takeover by Barney Barnato’s Johannesburg Estate Company in April 1889, unleashing a new era of ownership and regulation. Despite having its own General Committee, the JSE was fully dependent on the fixed assets and capital of the Estate Company, leaving it exposed to the regulatory dictatorship of Barney Barnato. Far more interested in membership fees and rent income from offices inside the JSE building, Barnato’s dominance came in direct conflict with the General Committee’s vision of growing the market for JSE-listed securities.

With different stakeholders advocating competing visions of institutional development, the first five years of the JSE’s existence tested the financial institution’s ability to balance the needs of regulation and promoting access to Africa’s largest capital market. Although a number of stock exchanges were already in operation on the African continent in the final quarter of the 19th century, the JSE emerged as a financial industry leader in what soon became the largest and wealthiest city in southern Africa. For all the eagerness and enthusiasm displayed by many Johannesburg-based speculators in expanding the volume and value of securities on the Official List, the development of the Exchange was constrained by the power struggle between the JSE’s General Committee and the Estate Company. By analyzing the JSE’s early rules and social organization, this study contributes to the better understanding of early stock exchange operation and organization in colonial South Africa.

References

Accominotti, O, Flandreau, M., & Rezzik, R. (2011). The spread of empire: Clio and the measurement of colonial borrowing costs. The Economic History Review, 64(2): 385–407.

Frankel, S. H. (1938). ‘Capital investment in Africa: its course and effects.’ Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lukasiewicz, M. (2019). Early regulation and social organisation on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, 1887-1892. Business History. Forthcoming.

Lukasiewicz, M. (2017). The making of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, 1880-1890. Journal of Southern African Studies 43(4): 715-732.

Lukasiewicz, M. (2014). ‘Reinvestigating Southern African stock markets in the late nineteenth century,’ South African Economic History Annual 3: 7-9.

Moss, T. (2003). ‘Adventure Capitalism: Globalization and the political economy of stock markets in Africa.’ Springer.

Rönnbäck, K., and O. Broberg. (2018). All that glitters is not gold: the return on British investments in South Africa, 1869-1969. Studies in Economics and Econometrics 42(2): 61-80.

Rosenthal, E. (1968). On ‘change through the Years: a History of Share Dealing in South Africa. Cape Town: Flesch Financial Publications.