As vaccines for Covid-19 become more readily available, the next challenge will be ensuring uptake of vaccines in developing countries. Despite numerous improvements in health technology and access, health interventions in developing countries often fail because of low demand by the final consumers (Dupas 2011; Dupas & Miguel 2017). For example, polio vaccination campaigns have been unable to reach herd immunity levels due to vaccination refusals in Cameroon (Kindzeka 2015). Thus, even once supply and technological issues have been addressed, health interventions often struggle during this “last mile” of implementation (Dupas 2011; Dupas & Miguel 2017).

One potential barrier to vaccine uptake may be due to mistrust in medicine and vaccinations. From the colonial era onwards, many people in developing countries have experienced past instances of medical malpractice and exploitation. How does this history of medical malpractice shape medical outcomes today, and how should policymakers take this into account during this next challenge of the pandemic?

In a recent study (Lowes & Montero 2021), we examine mistrust in medicine arising from historical exposure to colonial health campaigns in Central Africa. We focus on medical campaigns to combat sleeping sickness conducted by the French military in Cameroon and former French Equatorial Africa (AEF). These campaigns forced individuals, often at gunpoint, to receive treatment and prophylaxis for sleeping sickness using drugs with serious side effects. We link these campaigns to: mistrust in medicine, worse health outcomes, and lower World Bank health project success.

Description of the Campaigns

Between the 1920s and 1950s, the French military undertook extensive medical campaigns in sub-Saharan Africa aimed at managing tropical diseases. In Cameroon and former AEF (present day Central African Republic, Chad, Republic of Congo, and Gabon), the French military organized mobile medical teams to combat a variety of diseases, including sleeping sickness, leprosy, yaws, syphilis, and malaria. The most extensive of these campaigns focused on sleeping sickness, a lethal disease spread by the tsetse fly. Over the course of several decades, millions of individuals were subjected to medical examinations and forced to receive injections of various medications meant to either treat or prevent sleeping sickness. However, these medications had dubious efficacy and serious side effects, including blindness in up to 20 percent of individuals, gangrene, and death. The sleeping sickness campaigns constituted some of the largest colonial health investments, and for many, these campaigns were their first exposure to modern medicine (Headrick 1994; Pepin 2011; Lachenal 2014).

Medical Campaigns and Mistrust in Medicine

Motivated by work from anthropology and history, we hypothesize that the colonial medical campaigns may have had a series of unintended effects on both beliefs about modern medicine and the success of modern health interventions. Anthropologists and historians have linked the colonial medical campaigns against sleeping sickness to mistrust in medicine. For example, regarding tetanus campaigns in Cameroon in the 1990s, Feldman-Savelsberg et. al. (2000, p. 162) note, “[The tetanus campaigns] awakened negative collective memories of French colonial medical efforts to wipe out sleeping sickness”.

Measuring Campaign Exposure

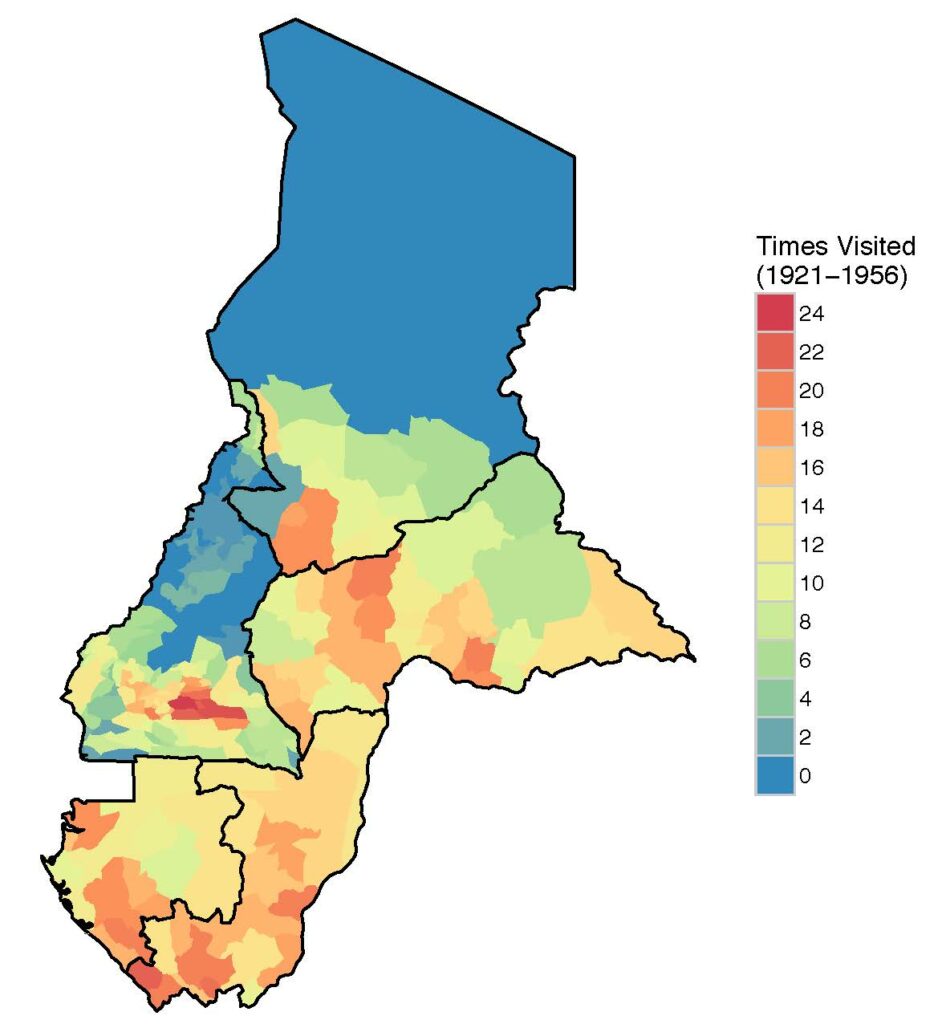

To measure exposure to colonial medical campaigns, we construct a dataset from over 30 years of archival data from French military archives for five countries. We digitize data documenting the locations of sleeping sickness campaign visits at a granular geographic level between 1921 and 1956. We measure exposure to the campaigns as the share of years that a location is visited during the years of the campaigns. See Figure 1 for a map of the distribution of campaign visits.

Figure 1: Map of campaign visits

Results: Campaigns, Vaccinations, and Mistrust in Medicine

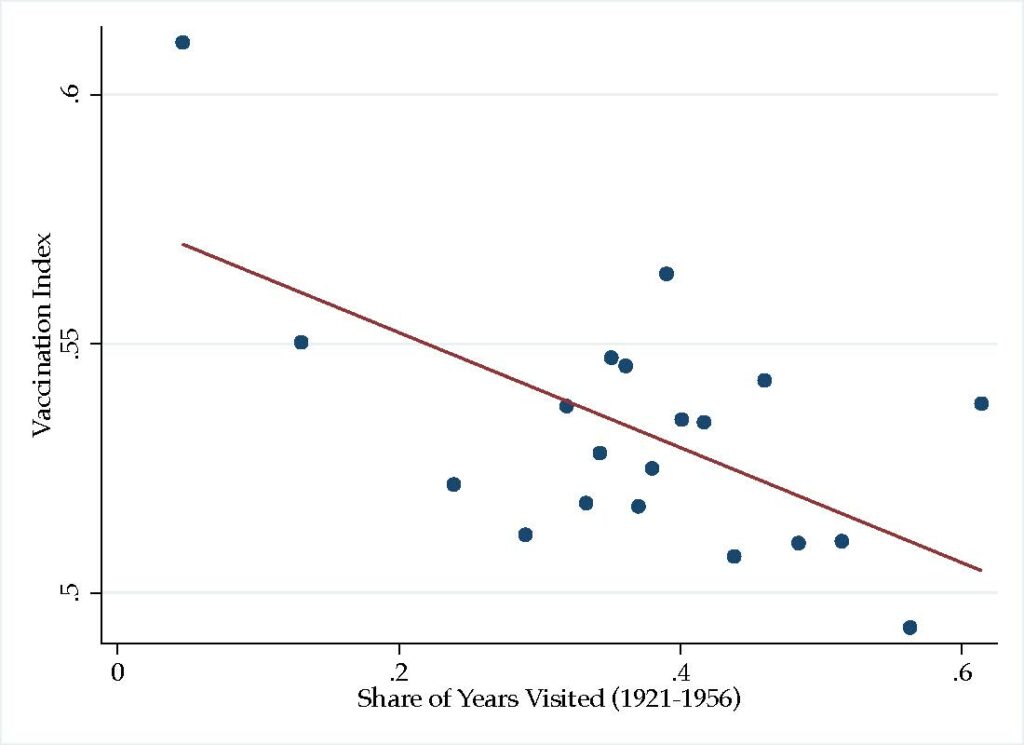

We focus on two key outcomes. First, we examine vaccination rates using data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) for our sample countries. In our area of interest, vaccination rates are low, often below herd immunity rates. We construct a vaccination index, which is the share of completed vaccines of nine possible vaccines for children under five.

Figure 2a shows that greater exposure to the campaigns is associated with lower vaccination rates for children. Being visited for 15 years, the average number of years an area is visited, is associated with a 5.8 percentage point decrease in the vaccination index relative to a mean of having completed about half of the nine vaccinations.

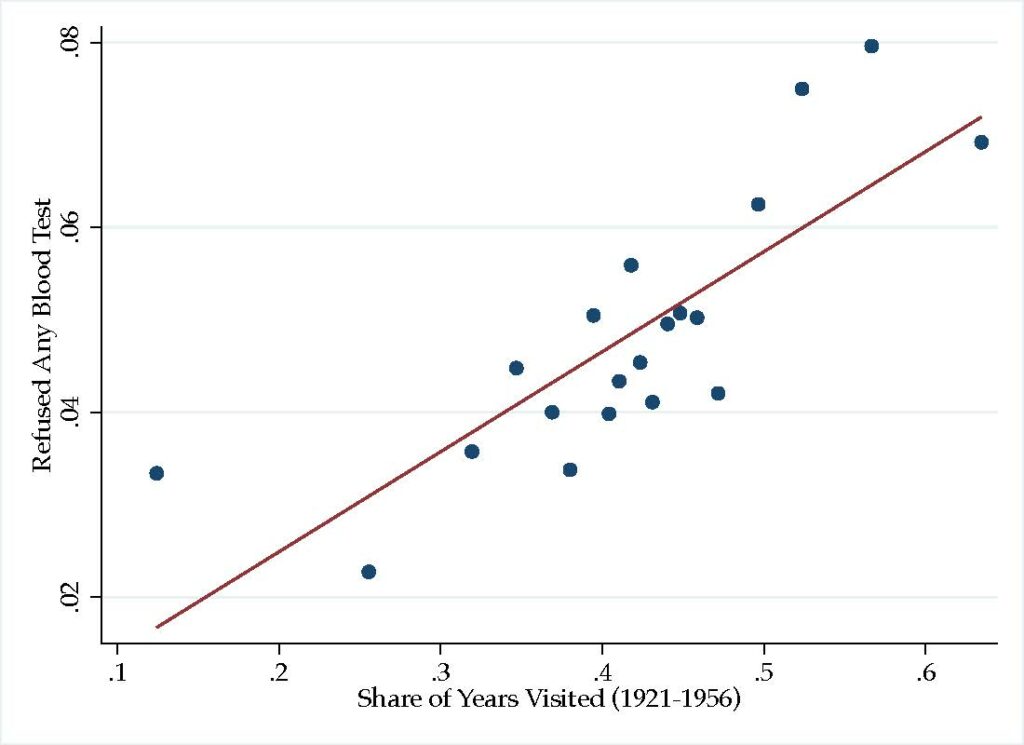

We then examine a potential proxy for trust in medicine. We measure trust in medicine by whether an individual consents to a free and non-invasive blood test for either anemia or HIV in the DHS. We consider consent to the blood tests to be a revealed preference measure of trust. Figure 2b shows that increased exposure to colonial medical campaigns is correlated with lower levels of trust in medicine today. Approximately 4.8% of the sample refuse the blood tests. Being visited by the colonial medical campaigns for 15 years increases refusals by 5.4 percentage points. The strong correlation remains when we examine anemia blood test refusals or HIV blood test refusals separately. Additionally, the results are robust to a variety of geographic, colonial, pre-colonial, and individual level controls.

Figure 2a: Impact of colonial medicine visits on vaccination indexes (binscatter plots)

Figure 2b: Impact of colonial medicine visits on blood test refusals (binscatter plots)

Trust in Other People or Institutions

We also explore whether the observed mistrust is specific to trust in medicine, or if it extends to trust in other people or institutions using Afrobarometer data from Cameroon and Gabon. We find that there is no effect of exposure to the medical campaigns on trust in a variety of non-medical individuals and institutions, suggesting that the effect of exposure to medical campaigns is specific to the medical domain.

Colonial Medical Campaigns and World Bank Project Success

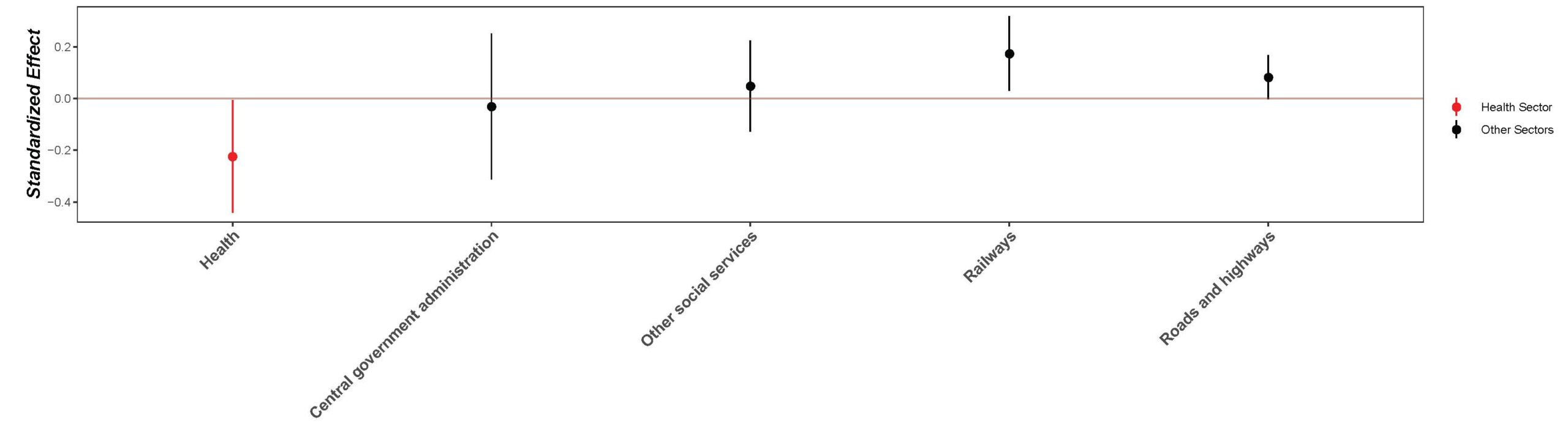

Finally, we examine the relevance of historical medical campaigns for present day health policy. We use data on the location of World Bank projects approved between 1995 and 2014 to examine how exposure to medical campaigns affects project success as rated by the World Bank. The World Bank rates projects on a 6-point scale from ”highly unsatisfactory” to ”highly satisfactory”. We compare the ratings of health projects and non-health projects by historical medical campaign intensity in Figure 3.

We find that greater exposure to the campaigns is correlated with lower health project ratings, but there is no similar effect on the ratings of projects in other domains. The effect size of historical medical campaigns for health project ratings for areas with the average exposure to the campaigns is equivalent to changing the rating from “moderately satisfactory” to “moderately unsatisfactory”.

Figure 3: Project rating coefficient plot (high res – zoom in for better view)

Conclusion

The historical medical campaigns provide several important lessons for present day development policy, which might be especially important in light of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. First, top-down aid implemented poorly and without local consent and involvement can have long lasting unintended consequences. Second, the success of present-day health interventions or policies may depend on the historical experiences of the target populations. Finally, building and maintaining trust in medicine should remain a priority for modern health policy.

References

Dupas, Pascaline (2011). “Health Behavior in Developing Countries.” Annual Review of Economics 3: 425-449.

Dupas, Pascaline, and Edward Miguel (2017). “Impacts and Determinants of Health Levels in Low-Income Countries.” In Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee, eds., Handbook of Field Experiments, Vol. 2, North Holland.

Feldman-Savelsberg, Pamela, Flavien T. Ndonko, and Bergis Schmidt-Ehry (2000). “Sterilizing Vaccines or the Politics of the Womb: Retrospective Study of a Rumor in Cameroon.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 14(2): 159-179.

Headrick, Rita (1994). Colonialism, Health and Illness in French Equatorial Africa, 1885-1935. Atlanta, Georgia: African Studies Association Press.

Kindzeka, Moki Edwin (2015). “Cameroon Finds Resistance to Polio Vaccination Campaign.” Voice of America News, 27 September 2015.

Lachenal, Guillaume (2014). Le Médicament qui Devait Sauver l’Afrique. The Hidden Story of the Medicine Meant to Save Africa. France: La Découverte.

Lowes, Sara, and Eduardo Montero (2021). “The Legacy of Colonial Medicine in Central Africa.” American Economic Review 111(4): 1284-1314.

Pépin, Jacques (2011). The Origins of AIDS. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press.

Featured image: This picture was taken in the context of an Ebola vaccine trial in Liberia. It bears no direct relationship to the article discussed in this blog post. The photograph was published under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license. Details: “April 3, 2017: Study volunteer receives inoculation at Redemption Hospital in Monrovia on the opening day in Liberia of PREVAC, a Phase 2 Ebola vaccine trial in West Africa. Credit: NIAID.