A large body of research has identified a negative correlation between fertility levels and population densities in pre-industrial societies – past and present (Doveri 2000). Fertility declines as land becomes scarce. A common explanation for this relationship is the land-labor hypothesis, which suggests that the demand for children as laborers is higher in newly established frontiers – so-called open frontiers – compared to older and more densely populated closed farming regions. This paper reconsiders the relationship between land availability and the presence of children in a settler frontier region: the Graaff-Reinet district at the eastern frontier of the Cape Colony, 1800-28. The question we ask is how the process of frontier closure affected the number of children present in settler households. In contrast to previous research, we find that the number of children present in the farming households increases with frontier closure.

Graaff-Reinet

The district of Graaff-Reinet, on the eastern frontier of the Cape Colony, was established in 1786. There, agro-climatic conditions favored pastoralism, and stock farming quickly became the dominant economic activity among the settlers. In contrast with the southwestern Cape, a salient feature of life on the frontier was the high proportion of virtually impoverished farmers (Newton-King 1999). They kept few slaves and instead mainly relied on the use of family and indigenous Khoisan as sources of labor. The period under investigation spans the closing of the Graaff-Reinet frontier, a process that was characterized by mounting population pressure, increased scarcity in natural resources and recurrent political tensions.

Data

We combine two newly transcribed datasets. The first is the annual tax censuses (opgaafrollen) (1663-1834) of all European households of the Colony. The records include information on the size and composition of the household as well as annual output and assets owned (Fourie and Green 2018). We use a sub-sample of these censuses for the Graaff-Reinet district covering the closure period (1800-28) supplemented with individual-level demographic data from the South African Families Database (SAF), through a novel automated record linkage strategy (Rijpma, Fourie and Cilliers 2019).

Findings

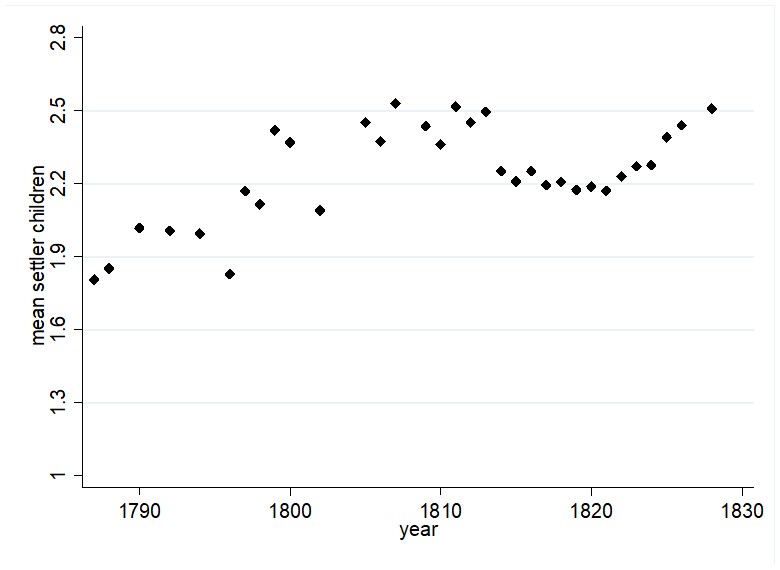

From Figure 1 we can see that the average number of settler children in frontier households steadily increased over the period of frontier closure in Graaff-Reinet. However, given the stark societal inequalities characterizing the frontier and trends in wealth over the life-cycle, we need to control for variation in wealth and age using a simple regression framework in which we estimate the association between capital and livestock wealth, the relative presence of non-family labor, and the number of settler children for all households over time.

Figure 1: Average number of settler children present in settler households, Graaff-Reinet, 1800-28

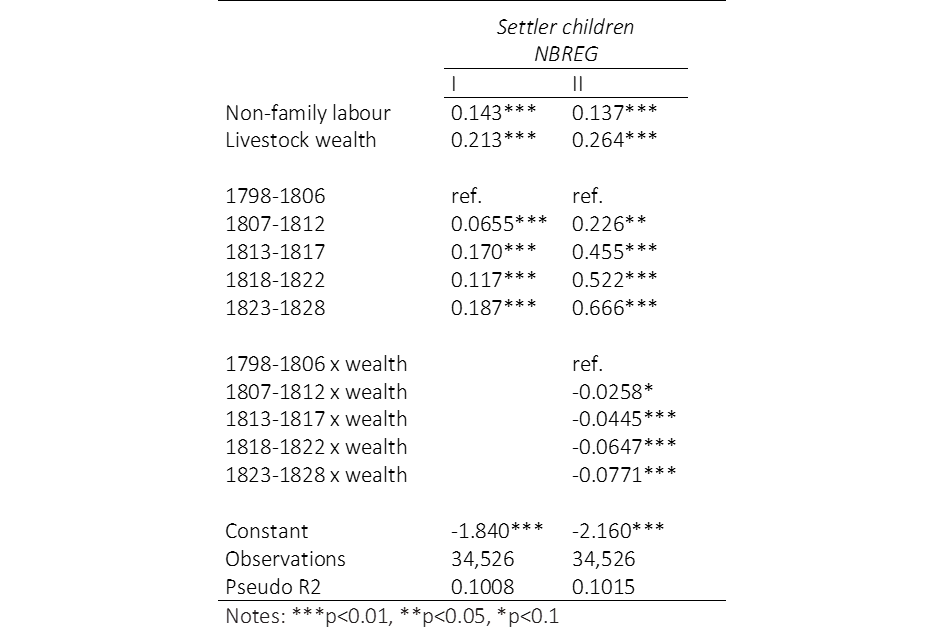

Table 1 summarizes our main result from a negative binomial model using the number of settler children present in a household as our dependent variable. We find a positive association between wealth and the number of settler children in frontier households. Over time, however, the number of settler children in frontier households is increasingly negatively associated with wealth. That is, while in absolute terms the wealthiest households report more settler children present, they begin to reduce the number of births over time. The wealthier responded to shrinking land availability by developing more capital-intensive methods as predicted by previous literature. The poorer, on the contrary followed a Boserupian strategy, i.e. employing more family labor to land despite shrinking marginal productivity. We deduce that the poorest households, being in majority and having more children over time drive the aggregate increase in children present in the settler households.

Table 1: Estimates from negative binomial model

We conclude that rural populations respond differently to shrinking land availability depending on their wealth. A rich farm household responds to diminishing land availability by substituting capital for labor, while poorer farmers respond by increasing their relative use of family labor. This strategy makes economic sense if we – different from the frontier literature – make a clear distinction between family and non-family labor. The employment of non-family labor is dependent on the marginal productivity of labor. This is not the case for family labor as shown by development economists, agrarian historians, and economic historians. On the contrary, in pre-industrial societies, poorer farmers will respond to shrinking land availability by adding more family labor to land despite its decreasing marginal productivity. This Boserupian path was what the majority of the Graaff-Reinet population followed.

References

Cilliers, J., and Green, E. (2018). The Land–Labour Hypothesis in a Settler Economy: Wealth, Labour and Household Composition on the South African Frontier. International Review of Social History 63: 239–271.

Doveri, A. (2000). Land, Fertility, and Family: A Selected Review of the Literature in Historical Demography. Genus 56: 19–59.

Fourie, J. and Green, E. (2018). Building the Cape of Good Hope Panel. The History of the Family 23(3): 493-502.

Newton-King, S. (1999). Masters and Servants on the Cape Eastern Frontier: 1760-1803. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge.

Rijpma, A., Cilliers, J., and Fourie, J. (2019). Record linkage in the Cape of Good Hope Panel. Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History: 1–16.