There has been renewed interest in the long-term effects of colonial-era Christian missionary activities on African economies today. Most of this work focuses on the long-run effects of missionary activities on human capital and its implications for society today. The general finding has been that missionary investments in education, healthcare, and the print media, have had persistent positive effects (Michalopoulos & Papaioannou 2020), although concerns about the precise role of missions relative to other colonial investments in the same areas remain (Jedwab et al. 2018).

Things Fall Apart?

While the literature on the human capital effects of missions has grown, relatively little is known about how Christian missionary activities changed traditional institutions, beliefs, and norms in African societies, and the effects of these changes. In a recent paper, Things Fall Apart? Missions, Institutions, and Interpersonal Trust (Okoye 2021), I investigate the effects of colonial-era Christian missions on present-day social capital, specifically interpersonal trust. Early writers recognized that beside human capital investments, and religious conversions (Nunn 2010), missions had profound effects on the social functioning of African societies. For example, in Chinua Achebe’s classic novel Things Fall Apart, an elderly man laments the denigration of traditional customs and effects on social capital:

He says that our customs are bad; and our own brothers who have taken up his religion also say that our customs bad…Now he has won our brothers, and our clan can no longer act like one. He has put a knife on the things that held us together and we have fallen apart.

(Excerpt from Things Fall Apart, Achebe, 1958, Ch. 20).

Taking this observation as departure point, I investigate the extent to which colonial-era Christian missions indeed have “put a knife on the things that held us together.” The analyses focuses on countries under British indirect rule, where Christian missionaries were largely responsible for “assaults upon customary religious observances” which extended into assaults on traditional authorities and institutions (Fields 1982). Our main finding is that individuals from ethnic groups or living in areas with more Christian missionary activities in the colonial period express significantly less interpersonal trust today as measured in the Afrobarometer Surveys.

Understanding Missions and Interpersonal Trust

Why are missions negatively associated with interpersonal trust today? My main hypothesis is that interactions between early Christian missionary activities, on one hand, and traditional institutions, beliefs, and norms, on the other, might explain some of the observed differences in interpersonal trust in Africa today. Missionary activities, by introducing new beliefs, norms, and alternatives to village life, changed the rules organizing traditional societies. The effects of missions were most keenly felt in colonies where traditional authorities remained in control of local administration, as under British indirect rule. New norms and beliefs of missionaries weakened traditional constraints and decreased cooperation with traditional norms and authorities. The belief in future cooperation, and trust, would then be adjusted downwards. I provide additional evidence consistent with the above hypothesis.[1]

Missions and Traditional Beliefs

I further use data from the Afrobarometer and Pew surveys (Gershman 2016), on traditional beliefs and practices, to show that historical exposure to missionary activities is robustly associated with a decline in attachment to traditional society, institutions, norms, and beliefs today. Specifically, I find that historical mission exposure is associated with decreased contact with traditional leaders, belief in juju and traditional gods, the use of traditional healers, participation in traditional rituals and initiation ceremonies, and moral acceptance of polygamy. All are important aspects of traditional institutions, society and religion, with polygamy being a major source of conflict between missions and traditional authorities. I do not find evidence that the effects are unique to mission type, Catholic vs. Protestant, nor specific mission investments. I do not find evidence that the effect is only restricted to Christians, and the estimates show that missionary activity is not negatively related to trust in the institutions adapted from the colonial era–such as the courts and the police, indicating that experiences with the colonial administration are not driving the results.

Missionary Expansion and Imprisonment in Nigeria

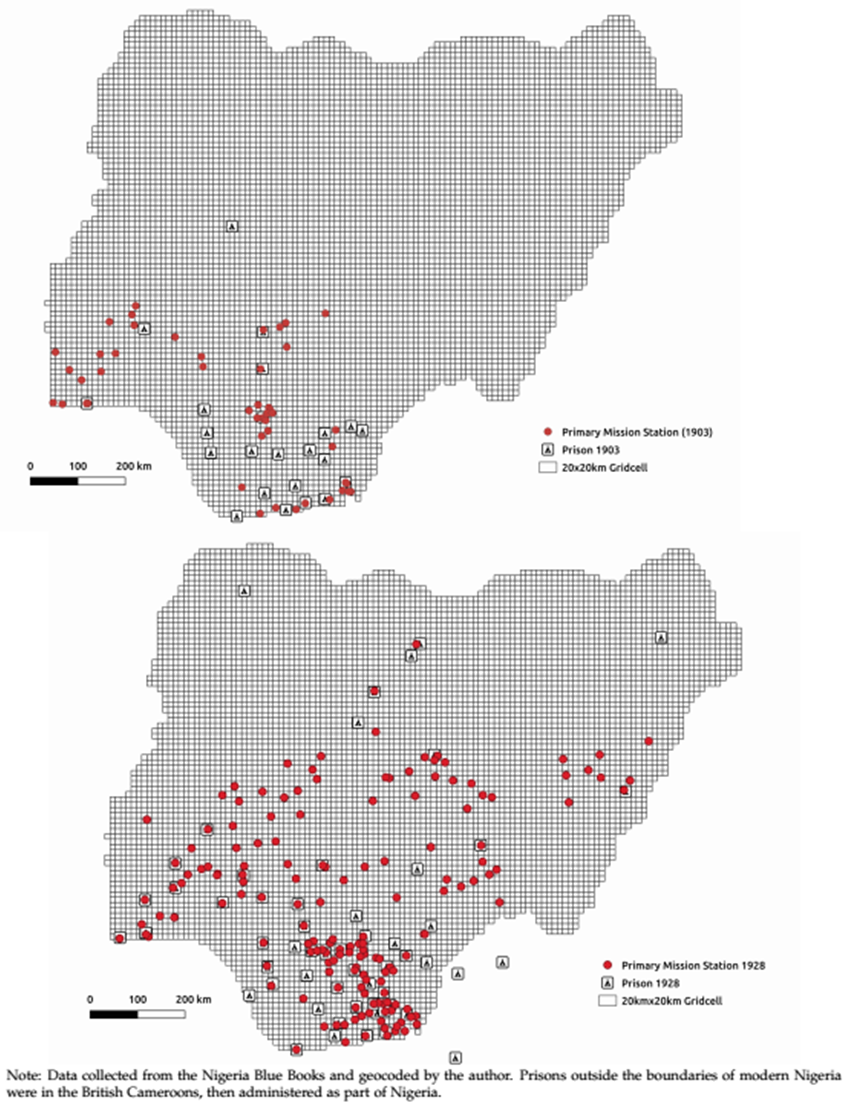

I also collect new data on colonial-era native authority prisons in Nigeria, which were largely established to deal with failing traditional sanctions, to investigate whether uncooperative behaviors, that could not be handled through traditional sanctions, increased as missions expanded. Prisons associated with native authority courts are informative in this regard because locals increasingly established and relied on them as traditional sanctions became less effective (Saleh-Hanna and Ume, 2008). The geospatial expansion of primary mission stations and prisons, between 1903 and 1928, is mapped in Figure 1.

As can be seen from the Figure, the earliest mission stations were on the coast, and in the interior of Southwestern Nigeria. By 1928, missions have expanded well into the interior of Southern Nigeria and made the push north along rivers, railways, and newly opened lines of communication. However, the push north was halted by the colonial policy restricting missionary activities in parts of Northern Nigeria, even as missionary societies protested (Ubah, 1988).

Figure 1: Mission expansion and prisons

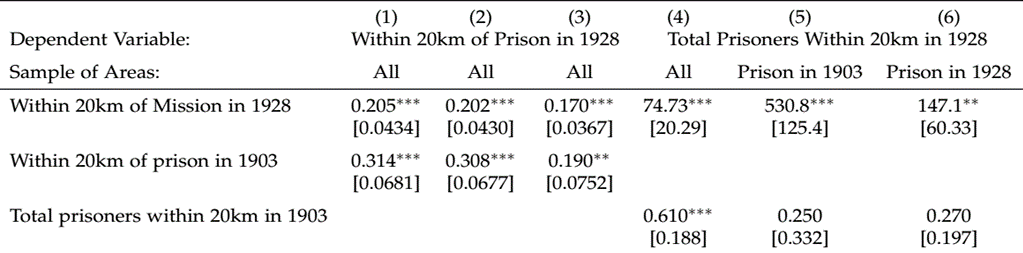

As shown in Table 1, I find that, conditional on 20km proximity to a prison in 1903, the expansion of missions between 1903 and 1928 is associated with an increase in the number of native authority prisons and prisoners over the same time period. The results demonstrate the falling apart of traditional authorities with the expansion of missions, as measured by increased reliance of prisons over traditional sanctions. This is true even if we only examined places within the same ethnic homeland and colonial province.

Table 1: Missions and Growth of Prisons and Prisoners

Conclusions

Overall, the study provides empirical support for colonial-era observations that missions made it difficult for traditional authorities to govern (Barnes 1995), and show that historical missionary activities are associated with significant declines in both colonial and present-day community life and traditional authority, and decreased cooperation as a consequence. The paper provides several examples from contemporary observations of these events that directly support the empirical findings.

I study the effects of missions as agents of acculturation and rivals to traditional institutions and norms. While the acculturation process has led to increased human capital in areas where missions operated, the cost is a decline in traditional culture and institutions with negative implications for trust today especially in countries where traditional institutions remain important. I believe that more studies are needed on the role of missions in shaping social capital in African societies, and on the importance of the breakdown in pre-colonial institutions on social cohesion today. This study is only a first step towards understanding wider impact of colonial-era social change on African societal life.

References

Achebe, C. (1958). Things Fall Apart. African Writers Series. London: Heinemann.

Barnes, A. (1995). ‘Evangelization Where It Is Not Wanted’: Colonial Administrators and Missionaries in Northern Nigeria during the First Third of the Twentieth Century. Journal of Religion in Africa 25(4): 412-441.

Fields, K. (1982). Christian Missionaries as Anticolonial Militants. Theory and Society 11(1): 95-108.

Jedwab, R., Meier zu Selhausen, F., & Moradi, A. (2018). The Economics of Missionary Expansion: Evidence from Africa and Implications for Development. CSAE Working Paper No. 7.

Michalopoulos, S., & Papaioannou, E. (2020). Historical Legacies and African Development. Journal of Economic Literature, 58(1), 53-128.

Nunn, N. (2010). Religious conversion in colonial Africa. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings 100(2): 147-152.

Okoye, D. (2021). Things Fall Apart? Missions, Institutions, and Interpersonal Trust. Journal of Development Economics 148: 102568.

[1] This is not to say that traditional norms and institutions remained intact under direct rule, but the that the destabilizing effects of missionary work was most keenly felt under indirect rule. Under indirect rule, some areas were able to effectively maintain traditional control while areas with intense missionary activities became destabilized. Under direct rule, this distinction became less stark and cannot be directly attributed to missions.

Feature image: File:ThingsFallApart.jpg – Wikipedia